“The way of progress was neither swift nor easy”: Taking a closer look at the legacy left by Marie Curie.

Marie Curie is a name with which most of us are familiar today, as the cancer hospices founded in her memory since 1930 continue to support and care for people living with cancer, and their families. However, while her scientific breakthroughs are now widely recognised and celebrated, Curie faced relentless gender discrimination throughout her life as documents in the forthcoming Gender: Identity and Social Change resource document. With 2018 termed ‘The Year of the Woman’ it seemed rather fitting to highlight Curie’s life-long struggle to overcome the patriarchal prejudices of her time to be recognised as an intellectual, a scientist, and ultimately a professional woman.

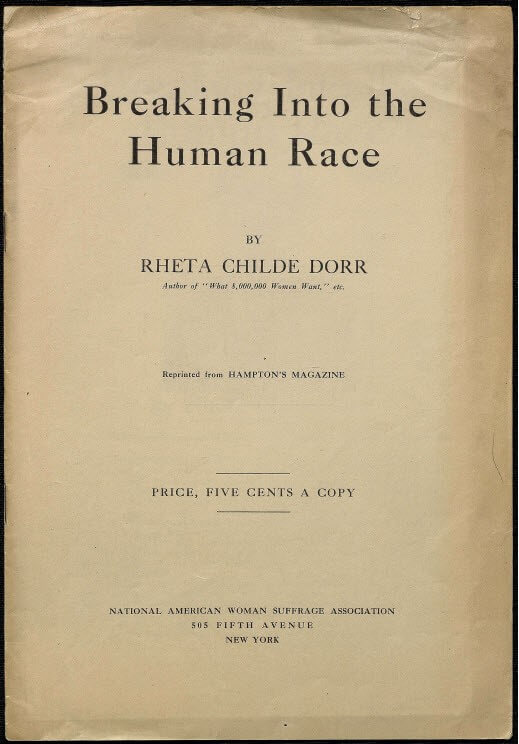

In her 1912 pamphlet “Breaking Into the Human Race”, Rheta Childe Dorr strove to dismantle the then dominating public view that “Women, being a sex, are expected to conform to a type, and they are admired and respected in proportion to their ability to conform”. Although Dorr refers to various women in the public eye to exemplify her point, her account of Marie Curie’s struggle to gain her scientific education forms the foundation of her argument.

After facing persistent gender discrimination in her attempts to gain admittance to a university education, Dorr narrates that “the doors of [sic] great laboratory were opened grudgingly to her [Curie]”. Even then The French Academy, Department of Science later admitted that Curie “was the foremost scientist in France … but as a candidate for the French Academy she did not even exist”. The reason for this: “it was possible for scientists to listen to a woman lecture on radio-activity. It was impossible for them to associate her with their after discussions of it.”

Although The French Academy were adamant that “A woman, whatever her intellectual qualifications, can no more become a member of an academy than the educated monkeys Consul […] for the same reason. Neither is Human”, Curie continue to practice and pursue a career in chemistry. Curie continued to challenge the convention that “The rights of being human is entirely monopolised by men”, successfully forging a place for women in the field of science when she won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1911. Until her death in 1934 Marie Curie continued to push the boundaries of both science and women’s status, and to this day remains the only woman to have been awarded the Nobel Prize twice.

Like Dorr’s pamphlet, many documents in Gender: Identity and Social Change go beyond simply recording what Martha Carey Thomas described as the, “historic disadvantage women of genius and talent born with aptitude for scientific research”. Instead, they capture the various ways in which numerous women strove to realise their shared goal of ensuring “the girls of the next generation are given favourable conditions for this higher kind of scholarly development”.

For more information, including free trial access and price enquiries, please email us at info@amdigital.co.uk. Gender: Identity and Social Change is available now.

All images © Bryn Mawr College. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Recent posts

James Prinsep, the son of an East India Company merchant and government official, holds a notable place in Indian history for his work in the Indian Mint and standardising currency. Records from East India Company, module VII show how Prinsep, and the British-run East India Company more broadly, reshaped India’s currency to suit their economic and administrative needs.

Foreign Office, Consulate and Legation Files, China: 1830-1939 contains a huge variety of material touching on life in China through the eyes of the British representatives stationed there. Nick Jackson, Senior Editor at AM, looks at an example from this wealth of content, one diplomat’s exploration of Chinese family relationships and how this narrative presented them to a British audience.