Teaching ‘History of The Civil Rights Movement’ with African American Communities and Race Relations in America

Researching and contextualising primary documents are the foundations of history instruction

What defines a city’s public space? Who designates such areas, who determines their uses, and who gets to use them? In his book, To Render Invisible: Jim Crow and Public Life in New South Jacksonville, Robert Cassanello investigated nineteenth-century Jacksonville to demonstrate that such questions have been part of urban life for more than a century.

As associate professor of history at the University of Central Florida, Cassanello brings these questions also into his teaching. The university is an innovative space, and Cassanello is in many ways at the forefront of this, curating museum exhibits and producing award-winning films and podcasts. However, talking to him, it becomes clear that teaching students the skill of researching and contextualising primary sources remains, to him, the foundations of history instruction.

Can you tell me more about your course ‘AMH 4575: History of the Civil Rights Movement’? Why have the primary sources in African American Communities and Race Relations in America been so useful for teaching this course?

Researching and contextualising primary documents are the foundations of history instruction. I teach a course on the history of the African American Civil Rights Movement in the United States, from its nineteenth-century origins to the 1960s victories to the problems of desegregation today. One of the key learning outcomes of the course is to comprehend and analyse the major themes in the Civil Rights Movement and place them within their historical context. The databases of primary documents in African American Communities and Race Relations in America provide students with a digital archive that is word searchable. Students can easily and online explore topics related to the Civil Rights Movement not covered in the class as well as stumbling onto a find that they can explore which may never have been published.

Students need to under understand the difference between viewing an original document and relying on someone else’s interpretation of the history these documents bear witness to.

Cassanello runs an introductory session to students on the databases. In addition to familiarising the students with navigating them, the emphasis of this introductory session is on asking questions about the types of primary sources they have access to. It is important that students do not read documents underpinned by white supremacist ideology from the period without being able to critically frame these sources, for example.

You described using a photograph of a scientist looking through a microscope to explain primary sources to students. Could you unpack this analogy?

I show students two photos. One is a scientist looking through a microscope alone in a room. I tell students that the scientist can be a proxy for the historian, the slide can be a proxy for the primary document and the microscope itself is the context we use to understand the primary document under examination. The second photo I show them is similar except there is a person standing behind the scientist looking through the microscope. I tell the students this person behind the scientist represents the history student reading a book on history. They themselves are not witnessing the original document but having that document interpreted to them by the scientist – a proxy for the historian – viewing the original document through the microscope.

One difficulty we face teaching with primary documents is the impulse of students to read documents as a literary artefact as opposed to interpreting primary documents using secondary sources.

What kinds of assignments do you set around the databases for students?

In each assignment, I introduce students to a seminal secondary work in the field and its thesis. From there students are required to explore African American Communities and Race Relations in America to locate documents that explain and create a context to their secondary reading on different eras or geographies. Through this, students demonstrate that they understand the ideas and theories in their literature reading and can apply and contextualise those ideas.

During one week of teaching, Cassanello introduced students to Glenn T Eskew’s seminal 1997 study, But for Birmingham: Local and National Movements in the Civil Rights Struggle. His students used African American Communities and Race Relations in America to explore sources on another city with an urban impact. His students developed an urban thesis and context to the Civil Rights Movement by investigating primary sources on cities like Atlanta, St Augustine and Greensboro in AM databases. Based on their research, the students gave presentations and wrote online posts with embedded links, with discussion actively encouraged underneath these posts. At the end of the course, the students write papers comparing their own primary source document to a different primary source chosen by another student.

Can you explain the importance to you of having students collaborate in an online environment?

The primary documents the students research are also shared with the rest of the students in class. They create a blog-style post in the class discussion section, where they can embed the actual document(s), write the context for the document based on their secondary reading, and explain why they selected this document to share. This represents an effective way to employ active learning in an online environment. One difficulty we face teaching with primary documents is the impulse of students to read documents as a literary artefact as opposed to interpreting primary documents using secondary sources. In the online discussion, students understand how their classmates are interpreting primary documents for the current lesson and learn from each other.

Can you describe the impact these primary source assignments have on your students’ learning?

I design assignments that require students to employ a thesis or context from a secondary source to an original document they research on their own in the databases. Because I am not assigning the primary document, but the students select and research this on their own to share with me and their classmates, this demonstrates to me higher order skills of analysis and examination as opposed to lower order skills of comprehension and recall. If the students can take a thesis out of secondary reading and utilise that thesis to support or refute the research of the author, then this would demonstrate to me that students are engaging with the course material at a very high level.

About the author

Robert Cassanello is a social historian interested in public history and an associate professor of history at the University of Central Florida. His book To Render Invisible: Jim Crow and Public Life in New South Jacksonville won the 2014 Harry Moore Award by the Florida Historical Society. His other books include Migration and the Transformation of the Southern Workplace since 1945 with Colin J Davis and Florida’s Working-Class Past: Current Perspectives on Labor, Race, and Gender from Spanish Florida to the New Immigration with Melanie Shell-Weiss.

Dr Cassanello’s public history projects have involved collaboration with over 25 museums, archives and historical societies across the state of Florida and he has produced award-winning films screened at national and international festivals. He also produces the award-winning podcasts RICHES of Central Florida and A History of Central Florida Podcast and is a featured voice on the weekly public radio program Florida Frontiers.

Recent posts

The University of Portland consolidated its digital assets and Scholarly Institutional Repository into a single, unified platform using AM Quartex, addressing inefficiencies and improving user experience. This transformation eliminated information silos, streamlined workflows and significantly enhanced the accessibility and discoverability of digital assets for both administrators and end-users.

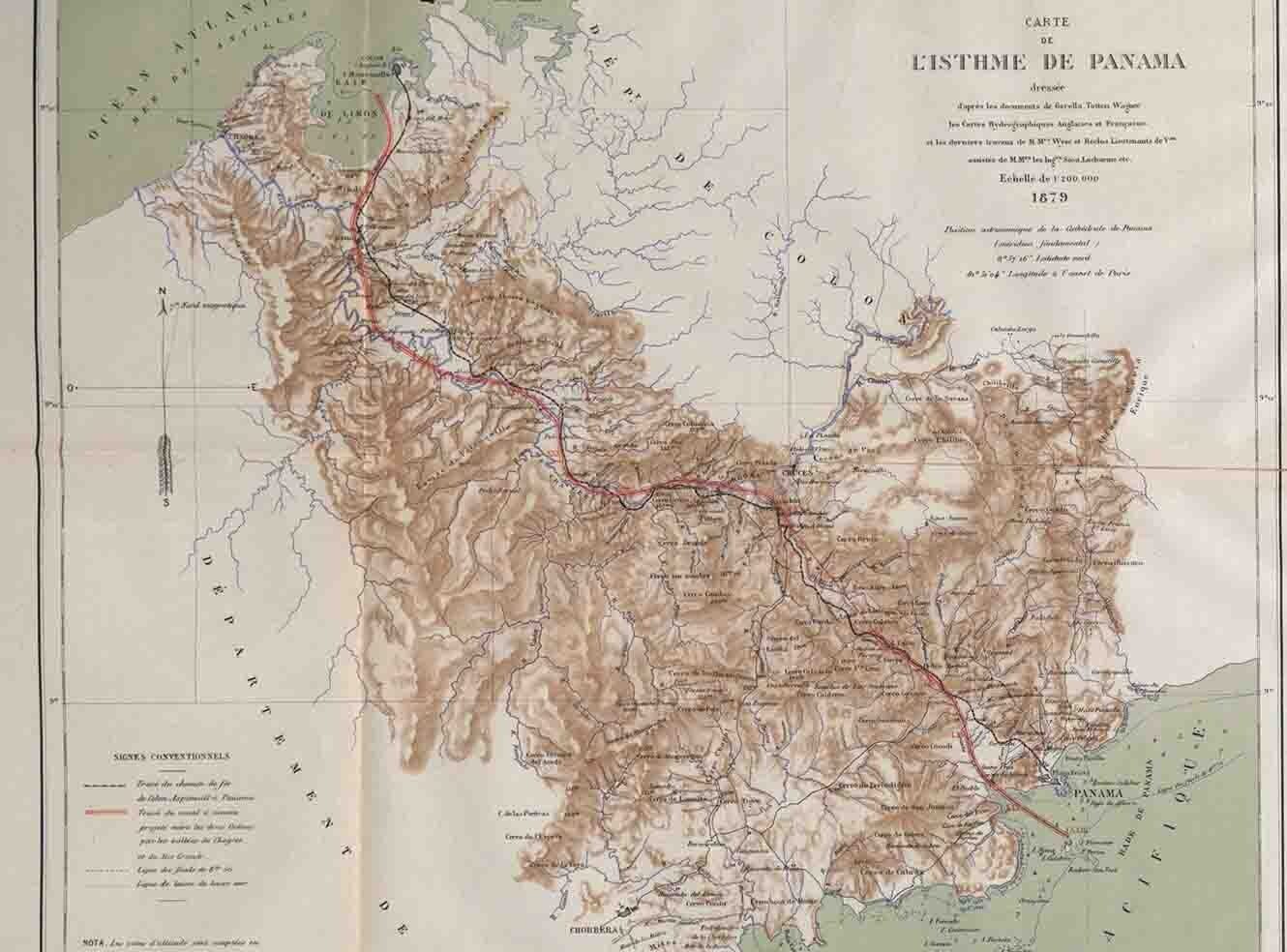

Professor María Cecilia Zuleta, a research professor at El Colegio de México (COLMEX) discusses how she has leveraged Confidential Print: Latin America found within the AM Archives Direct series. The resource has been key for the institution, advancing multidisciplinary research, allowing in-depth exploration of the links between foreign trade, economic modernisation, and the rise of fossil-based economies.