“What happened to reform, Mr Botha?”

2024 seems to be the year for momentous elections. In just the past month, Labour have won a landslide victory in the UK, a left-wing alliance has seen off the far-right in the French elections, and, after weeks of negotiations, South Africa’s president Cyril Ramaphosa has finally unveiled the new coalition government after his party, the African National Congress (ANC), lost its majority for the first time in 30 years. This year also marks the 40th anniversary of another significant general election in South Africa, notable for very different reasons: as the first election under South Africa’s new constitution it represented a pivotal moment in the liberation struggle.

Proposed by then-Prime Minister P W Botha, this so-called ‘tricameral constitution’ introduced two new separately elected chambers in addition to the existing House of Assembly. The new House of Representatives and House of Delegates represented – and were elected by – South Africa’s Coloured and Indian populations respectively, the first example of power sharing since the policy of apartheid was first implemented in 1948.

However, two aspects of Botha’s reforms saw widespread criticism. Firstly, the relationship between the three chambers was structured as to place power overwhelmingly within the white House of Assembly, which could not be outvoted by the other two chambers. Moreover, the new constitution continued to disenfranchise South Africa’s majority Black population, who had no representation in parliament and could not vote.

This constitution which became law on 3rd September 1984 has been widely rejected because it entrenches the rightlessness of the African majority in this country.

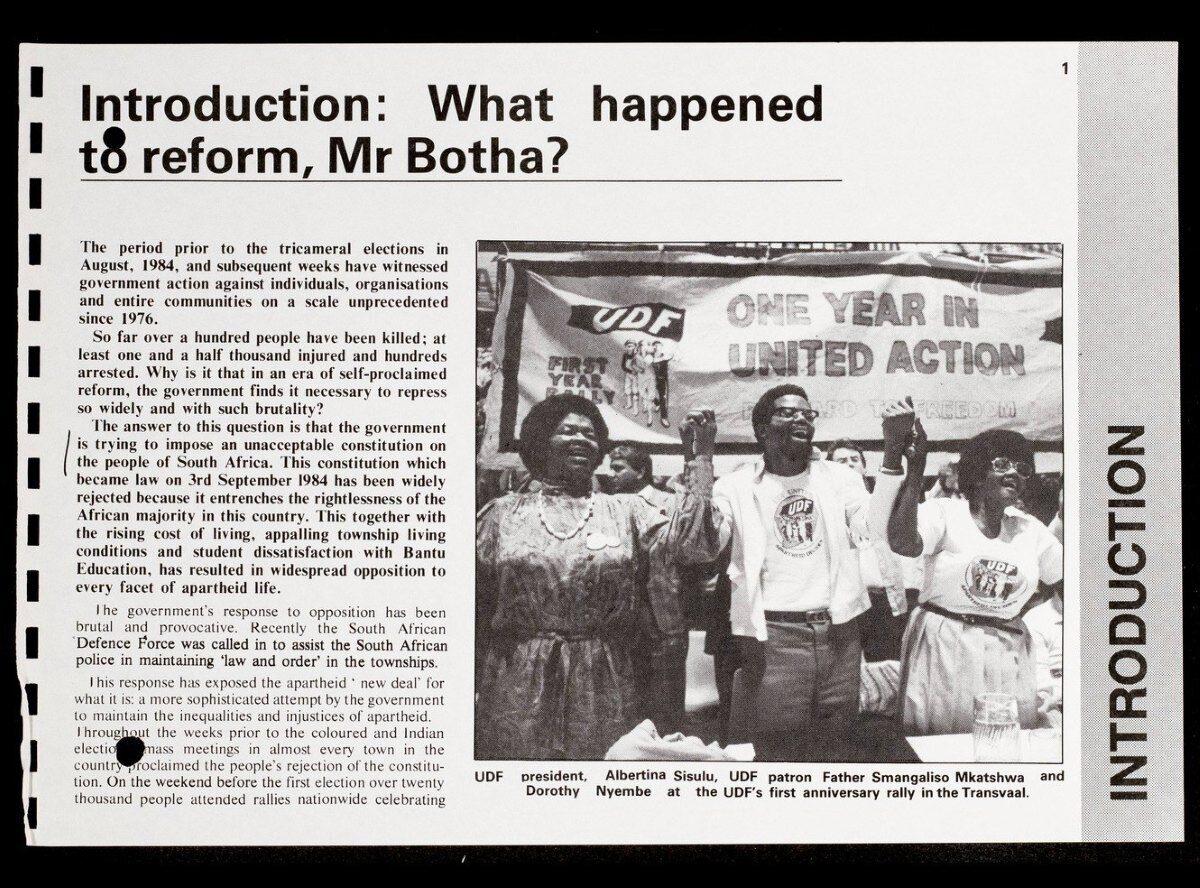

Opposition to the tricameral constitution was spearheaded by the United Democratic Front (UDF), a vast and decentralised coalition of anti-apartheid protest groups, spanning trade unions, churches, student and youth organisations, sports bodies and women’s associations. The first goal of the UDF was to challenge the legitimacy of Botha’s reforms through a mass boycott of the 1984 election.

FCO 105/1984 – ‘Repression in a time of ‘reform’ Images, including Crown Copyright images, are reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England. www.nationalarchives.gov.uk’

The apartheid regime’s response was immediate and severe. The government launched a propaganda campaign, distributing falsified pamphlets with misleading information intended to discredit the UDF and sow discord among other protest groups. Meetings were banned or disrupted by security forces; activists were attacked and harassed by police; on the eve of the 1984 election, a number of UDF and other opposition leaders were arrested and served with ‘preventative detention’ orders.

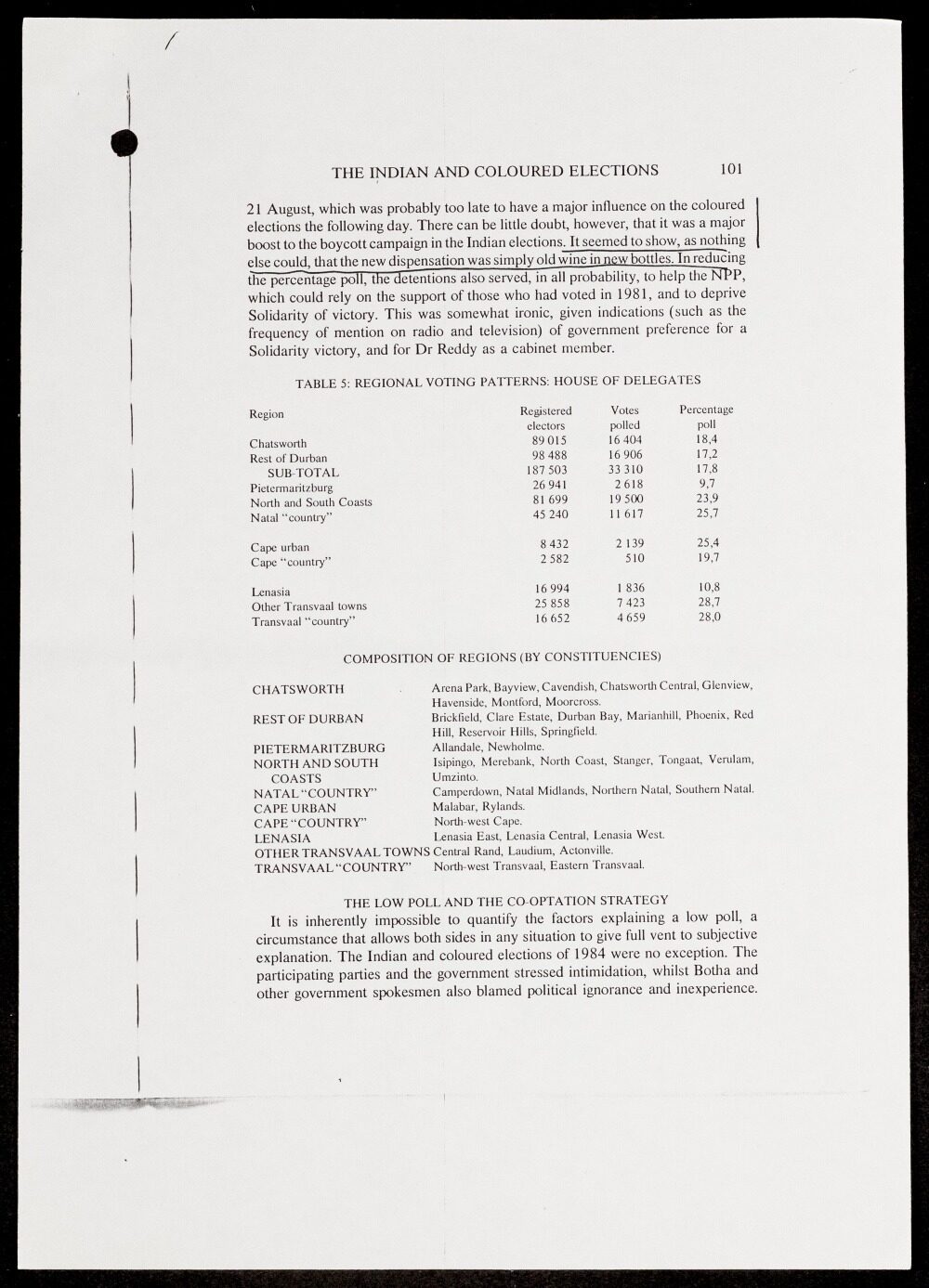

FCO 105/1702 – ‘Extracted page from an article on the 1984 election. Images, including Crown Copyright images, are reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England. www.nationalarchives.gov.uk’

Yet documents within AM resource Apartheid South Africa 1981-1988: Resistance, Sanctions and Reform speak to the broad success of the UDF and its allies in the face of this intense repression. As this article on the 1984 election shows, UDF-led boycott was so effective that in some regions as few as 9.7% of registered electors turned out to vote, a clear rejection of Botha’s reforms and a challenge to the legitimacy of the government.

More importantly, the boycott of the 1984 general election marked a symbolic new beginning for the anti-apartheid movement, inspiring further action against the apartheid government. In the months following the election, the Vaal Civic Association, an affiliate of the UDF, launched a new campaign to protest rent increases. Over the following years, South Africa saw an unprecedented period of insurrection against the apartheid regime.

About the author

Alex Barr is an Assistant Editor at AM.

About the collection

Apartheid South Africa 1981-1988: Resistance, Sanctions and Reform is out now. The document featured in this blog, is open-access for 30 days and can be found here:

Recent posts

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.