Unicorns: 'fierce and extremely wild?'

Recently digitised for Adam Matthew Digital’s Age of Exploration, the papers of Sir Joseph Banks offer fascinating insights into European maritime exploration, scientific developments and the intellectual life of his day. As well as accompanying Cook on his first voyage to the Pacific, Banks patronised numerous expeditions, and played a leading role in European academia. The range of individuals who corresponded with Banks is astounding; his correspondents include the naturalist Peter Simon Pallas, the astronomer William Herschel, the polymath explorer Alexander von Humboldt, and even revolutionaries (Benjamin Franklin and Jean-Paul Marat.) Likewise, Banks’ papers have a global reach, sent from or describing territories in both the new and old worlds.

However, some areas remained virtually inaccessible to Europeans, even during Banks’ lifetime; and in February 1820, a Major Latter reported to a Lieutenant-Colonel Nichol that he was convinced that unicorns existed in Tibet. A copy of this letter found its way into Banks’ papers (BL Add MS 33982, ff. 203-5), although it may not have reached Britain until after his passing.

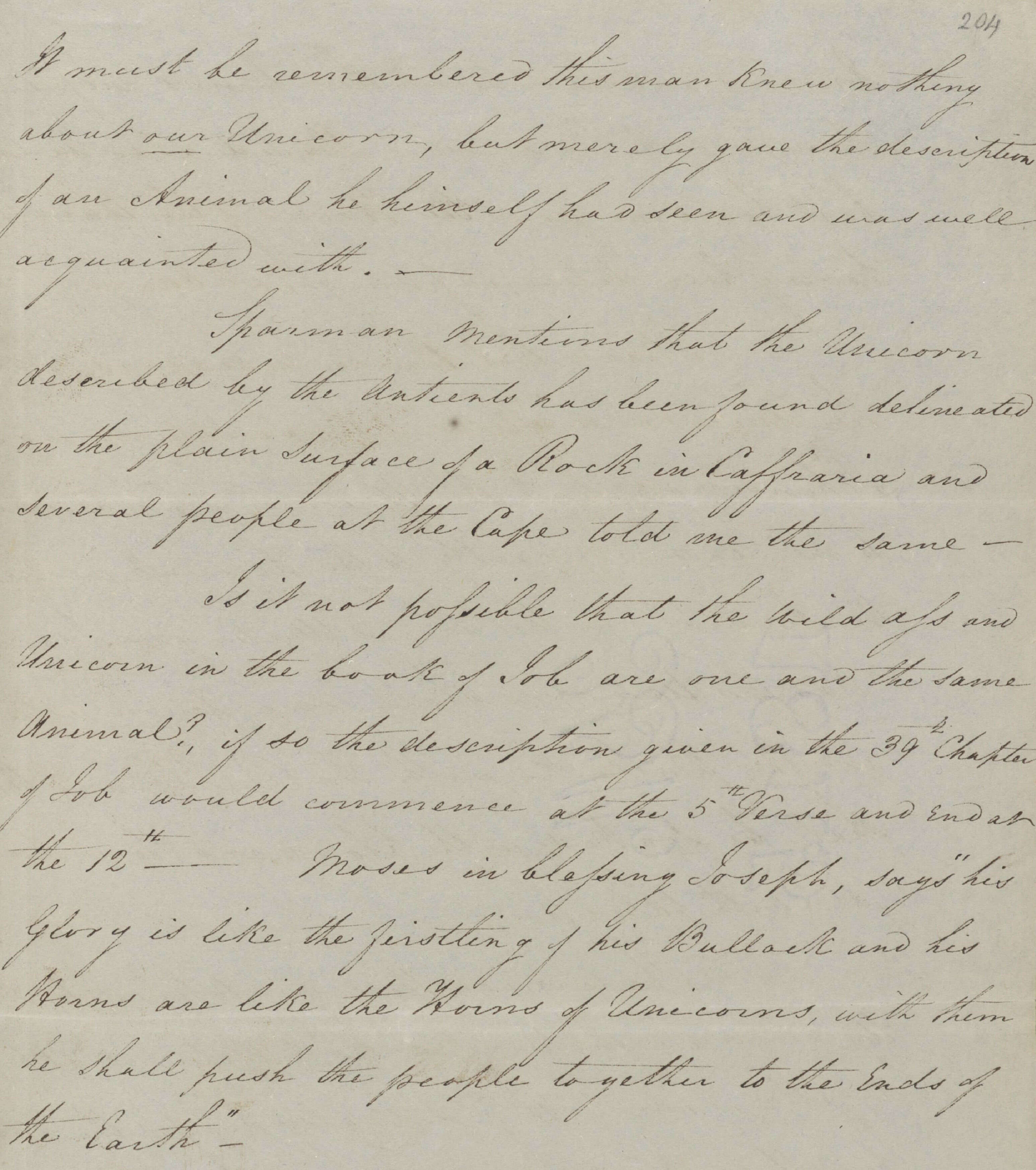

Latter noted that the ‘unicorn, so long considered a fantastic animal, actually exists in Thibit [sic] and is well known to the inhabitants’. This insight was gained from a man who had produced a manuscript which described such an animal, and apparently witnessed them in real life; Tibetan unicorns were ‘fierce and extremely wild… seldom caught alive but frequently shot and the flesh is used for food.’ Evidently aware that others might dismiss his letter (after all, he had opened it by mentioning that this news might be passed on to Lord Hastings, the Governor-General of India), Latter added that his encyclopaedia described the unicorn of antiquity as most likely an oryx, and that ‘this man knew nothing about our unicorn, but merely gave the description of an animal he himself… was well acquainted with’. Similar animals, he continued, were also described in the Bible, and had been observed in rock art.

Latter had approached the Sachia Lama, requesting that he send ‘a perfect skin of the animal, with the head, horn and hoofs’, but it would be ‘a long time before I can get it down’; herds of wandering unicorns could apparently be found ‘about a month[’]s journey from Lhasa’.

Prior to the European reconnaissance, people with dogs’ heads or enormous feet which could be used as a parasol had been thought to inhabit parts of Africa and Asia. These ideas were dismissed as more came to be known of these continents; but even in 1820, so little was known of Tibet in Britain that Latter’s story seemed sufficiently credible for it to be passed on for the consideration of a respected naturalist.

Age of Exploration is available now. For more information, including free trial access and price enquiries, please email us at info@amdigital.co.uk.

Recent posts

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.