“The workhouse looms before us”: Administering the New Poor Law

In 1834, the system of relief for the poor in England and Wales was overhauled by the Poor Law Amendment Act. This aimed to re-organise and centralise the administration of poor relief across the country, establishing deterrent workhouses and strict regulation of outdoor relief to reduce escalating relief costs. Within Adam Matthew’s newly released Poverty, Philanthropy and Social Conditions in Victorian Britain, it’s possible to explore the complex details of this new legislation’s implementation, as well as its accompanying social, political and economic repercussions.

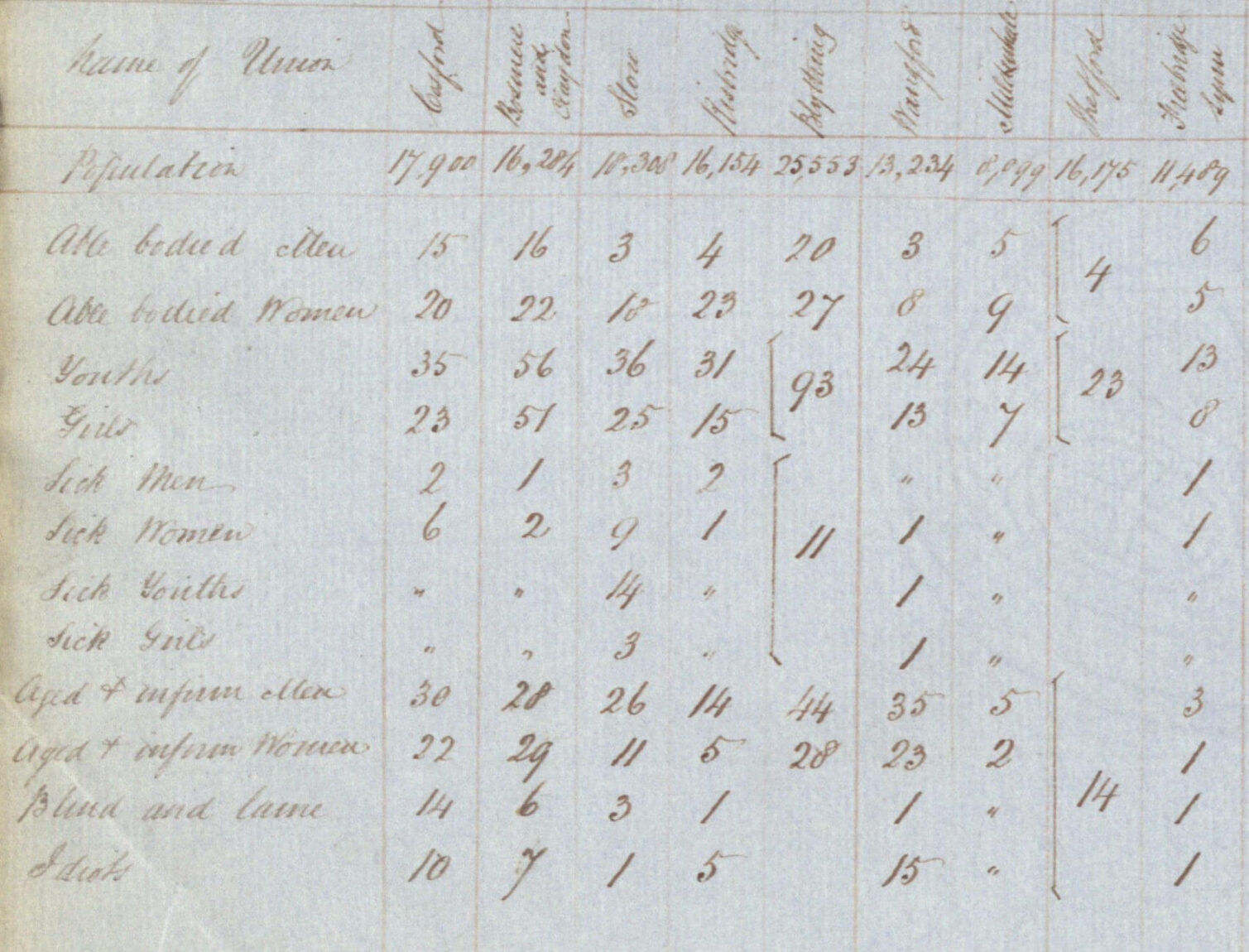

The official correspondence and papers of Assistant Poor Law Commissioners and Inspectors, digitised from the National Archives UK, offer a fascinating insight into the application of the New Poor Law and its evolution, as theory became subject to the reality of practice. Charged with enforcing and monitoring the New Poor Law across the country, Assistant Commissioners documented their visits to designated Poor Law Unions and workhouses, recording not only their evaluations of workhouse conditions, but also numerical data to be collated and analysed. A key aspect of this data collection was the classification of the poor into specific identifying categories. The correspondence and papers of James Phillips Kay-Shuttleworth, a Commissioner who oversaw the “Eastern district” including Norfolk and Suffolk, for example, demonstrate how reports on the “inmates” of workhouses were recorded according to sex, age, physical health and disability.

Union workhouse population summary, from James Phillips Kay (later Kay-Shuttleworth), correspondence and papers related to the Eastern District, 1837-1838 © Images including crown copyright images reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England. www.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

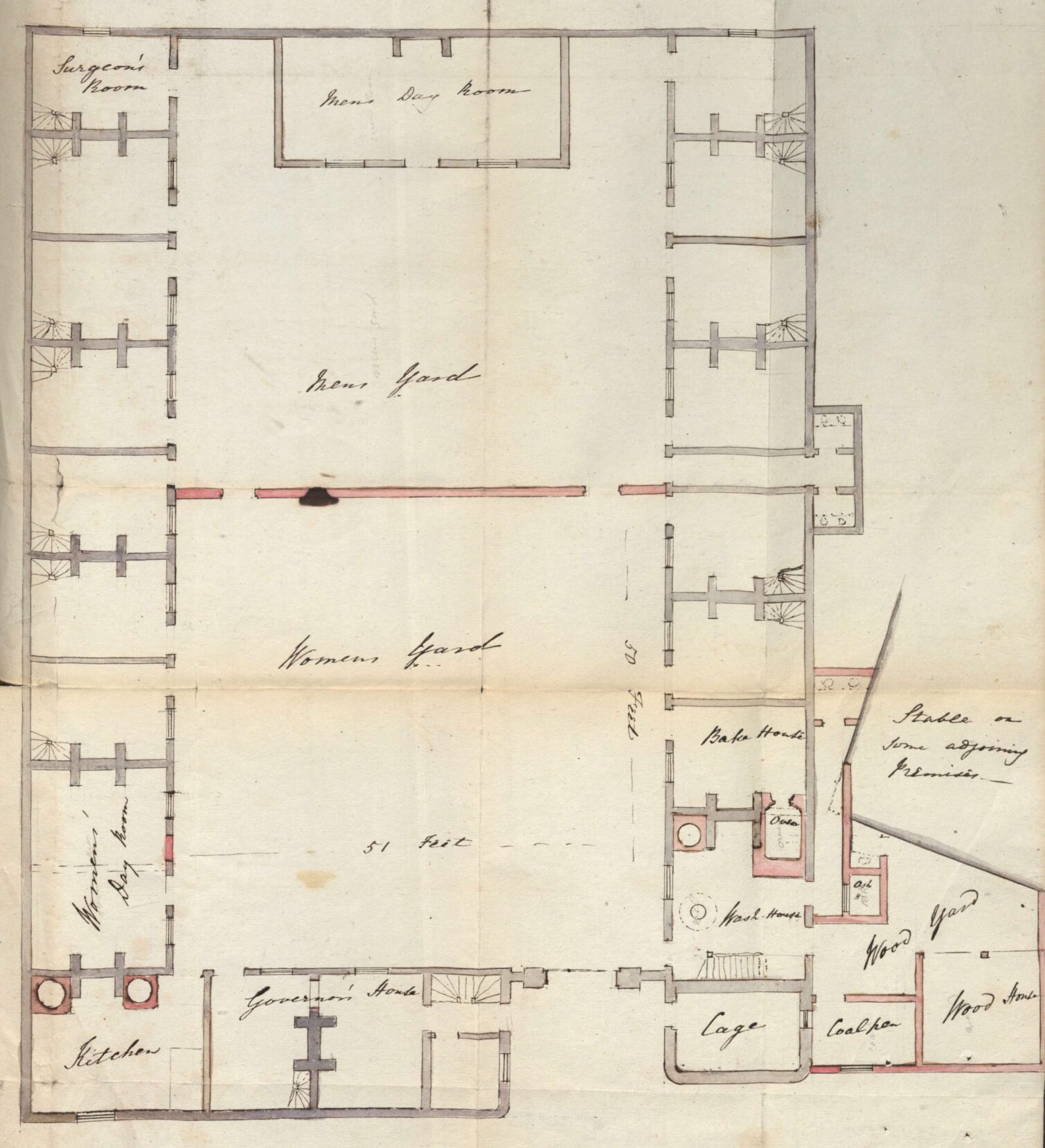

The workhouse occupants are further grouped by the term “able-bodied” which was largely used to identify those who were and were not capable of labour and thus of earning a living. This classification was not merely for administrative purposes; it also informed the layout and architecture of the workhouses, as can be seen in the floorplans included in the papers of Assistant Commissioner Colonel A C a'Court.

Plan of the Poorhouse at Hursley, from Colonel A C a'Court, correspondence and papers relating to the South Eastern District, 1834 © Images including crown copyright images reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England. www.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

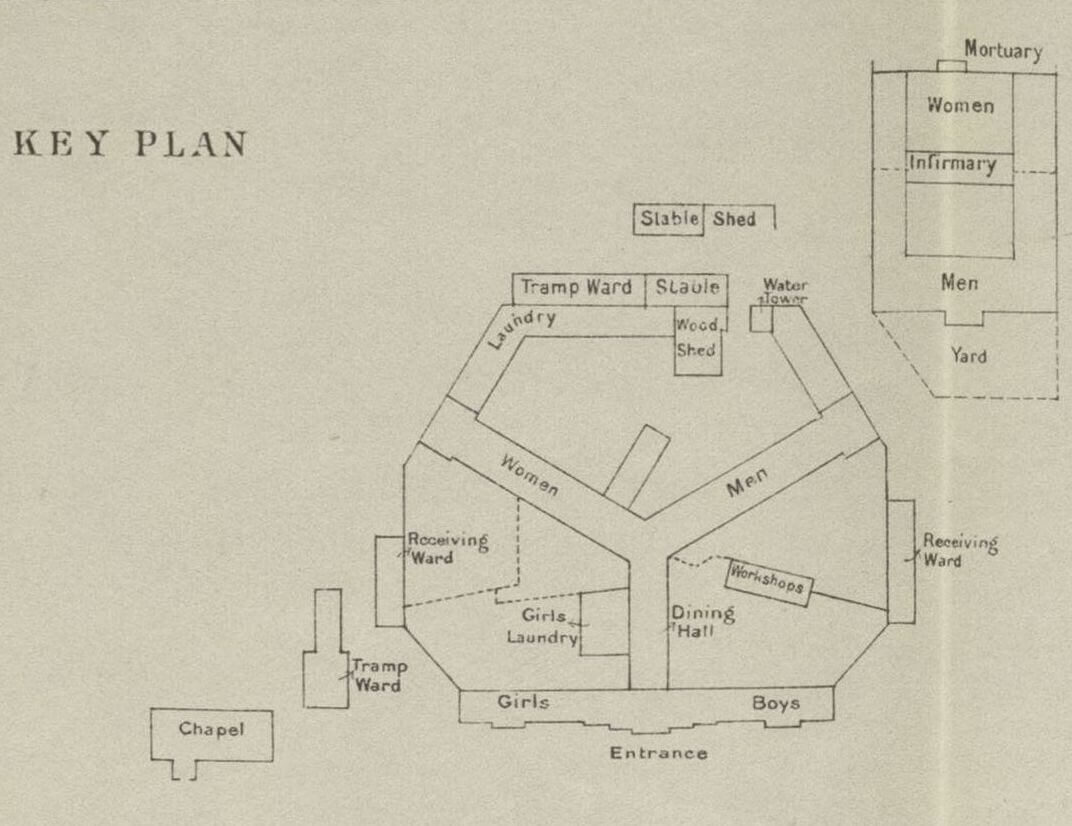

As the New Poor Law became increasingly established, the classifications were expanded upon and standardised: Article 98 of the 1847 Consolidated General Order divided paupers admitted to workhouses into seven distinct classes, including divisions between the able-bodied and infirm. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, these classifications for both indoor and outdoor relief were still under scrutiny, and the possibility of further, more complex sub-divisions and definitions continued to be the subject of much debate. The 1902 plan of Bradfield Union Workhouse from Annual report of the Board of Guardians and Rural District Council, digitised from the Family Welfare Association Library collection housed at the Senate House Library, demonstrates this increased complexity in its layout.

Plan of Bradfield Union Workhouse, from Annual report of the Board of Guardians and Rural District Council, 1902 © Images reproduced courtesy of Senate House Library, University of London.

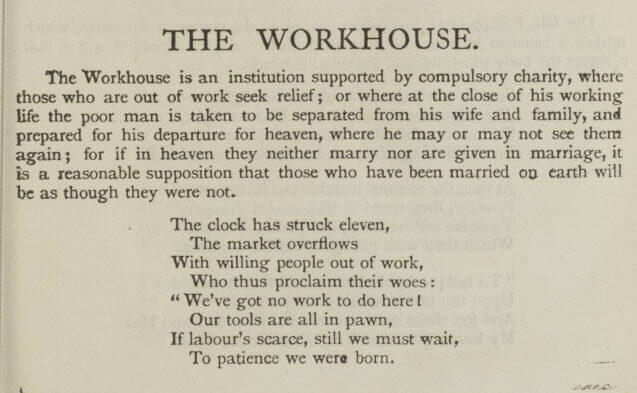

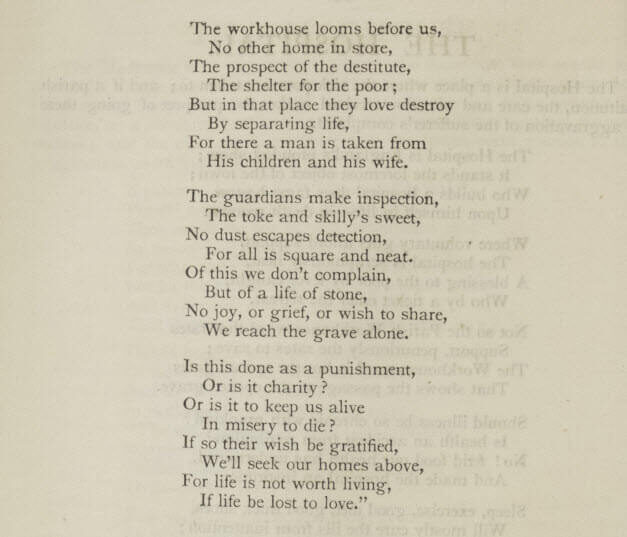

Accompanying this administrative and consequently objective documentation of the workhouse system, Poverty, Philanthropy and Social Conditions in Victorian Britain also includes material detailing the impassioned arguments of social reform groups in response to – and often in opposition to – the New Poor Law. Not least amongst these is Poetry of the Pavement, a “deprecatory” collection of poetry “by the Secretary of the Comprehensionists”. One poem, "The Workhouse", paints a melancholy picture of the consequences of classification for those individuals unfortunate enough to be its subject:

“The Workhouse”, from Poetry of the Pavement, 1870 © Images reproduced courtesy of Senate House Library, University of London.

“The Workhouse”, from Poetry of the Pavement, 1870 © Images reproduced courtesy of Senate House Library, University of London.

The last vestiges of the Poor Law lingered well into the twentieth century, with the United Kingdom’s last workhouses (by this time known as Public Assistance Institutions) closing their doors for the final time in 1948. Many of the buildings still stand, though repurposed, across the country. These newly digitised sources share the cold detail of the workhouse system, whilst also highlighting the work of the philanthropic and social reformist movements that arose in its looming shadow.

Poverty, Philanthropy and Social Conditions in Victorian Britain including free trial access and price enquiries, please email us at info@amdigital.co.uk.

Recent posts

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.