The Treaty of Versailles: differing perspectives

One hundred years ago today and after six months of protracted negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference, the Treaty of Versailles was signed. The treaty formally ended the war between Germany and the Allies and saw the formation of the League of Nations, an intergovernmental organisation with the mission of resolving international disputes.

Herbert A Olivier, Sketch of the Table in the Hall Of Mirrors, at Which the Treaty of Versailles was Signed © Imperial War Museums. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

The treaty also imposed terms on Germany. One of the many provisions was the controversial Article 231, later known as the War Guilt clause: Germany was to accept responsibility, alongside Austria-Hungary, for causing the First World War.

The treaty has been the subject of contentious debate among historians ever since. Some have pronounced it ‘history’s most hated treaty’ and blamed it for paving the way for the Second World War, and others, and sometimes both, have argued that the peacemakers did the best they could in difficult circumstances.

But what did people at the time make of the negotiations and of the treaty? Our First World War resource reveals different attitudes in correspondence, diaries and camp newspapers.

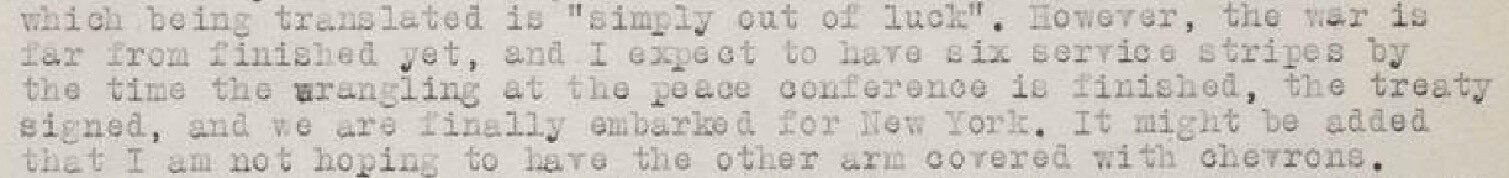

For instance, American soldier Jacob Adams Emery writes to his mother on the 11th August 1918 about the lengthy peace negotiations:

Image © Hoover Institution Library and Archives. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

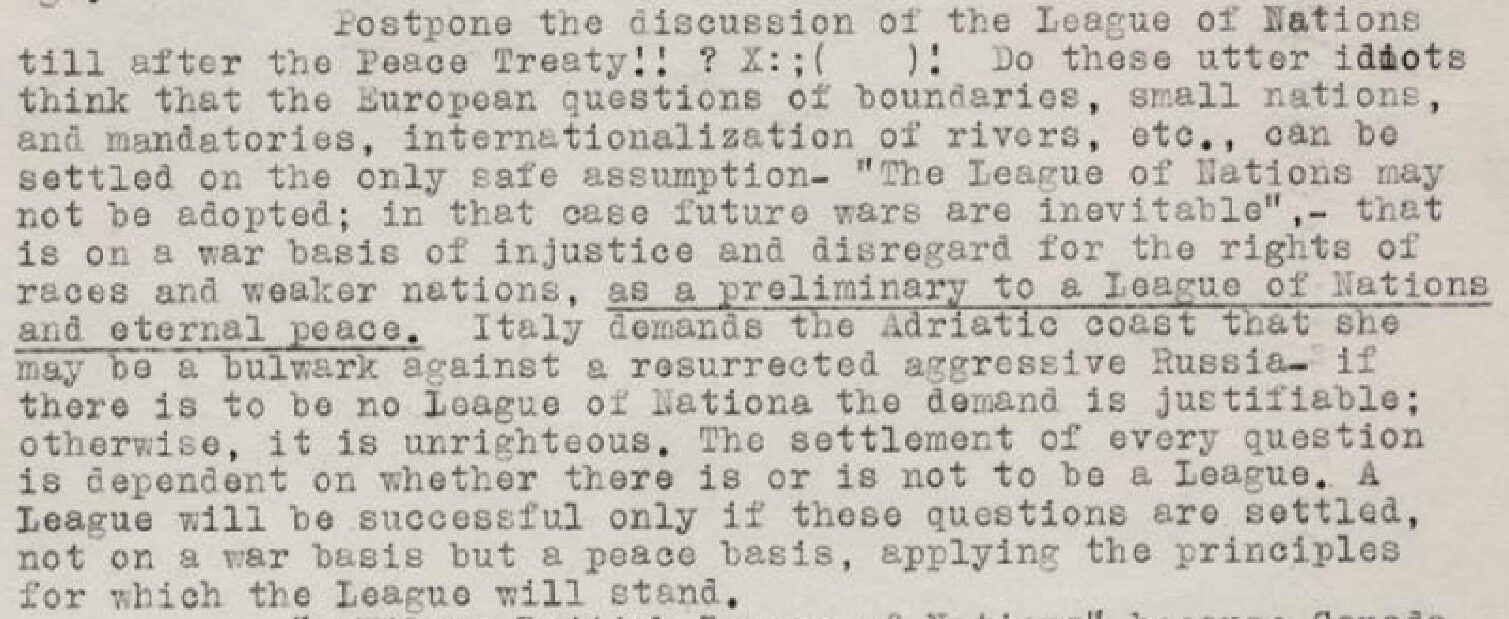

He also expresses anger at the proposition to postpone discussions surrounding the League of Nations until after the peace treaty:

Image © Hoover Institution Library and Archives. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

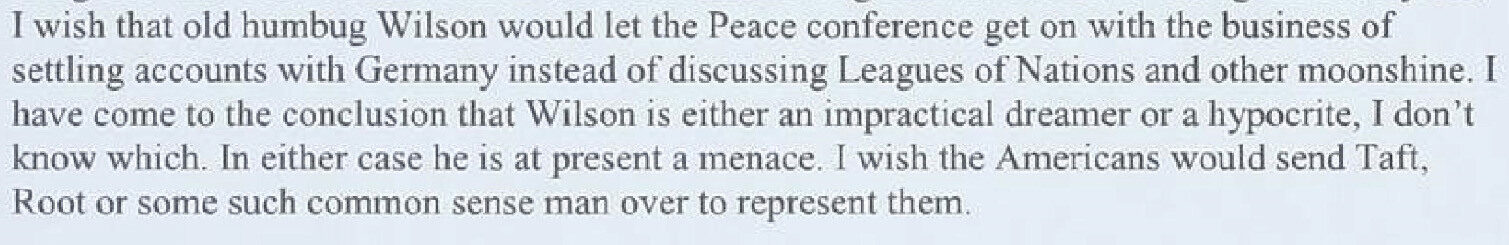

In contrast, Canadian Medical Officer Harold McGill conveys frustration at US President Woodrow Wilson’s championing of the League of Nations in a letter to his wife from the 16th February 1919:

Image © Glenbow Museum. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

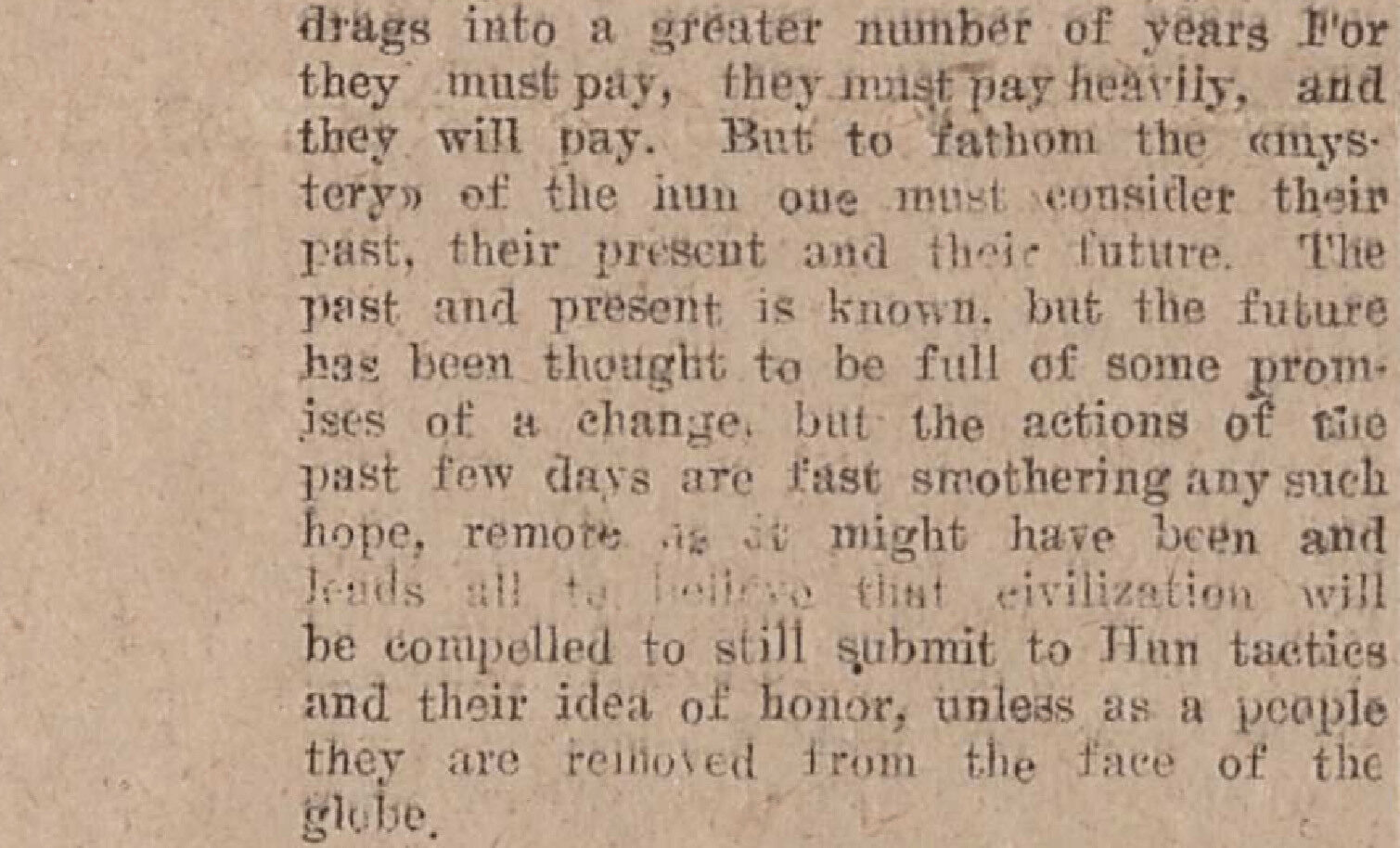

On the day the treaty was signed, an article in The Amaroc News maintains: ‘For they [the Germans] must pay, they must pay heavily, and they will pay’:

The Amaroc News, 28 June 1919, Image © National WWI Museum at Liberty Memorial Archives. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

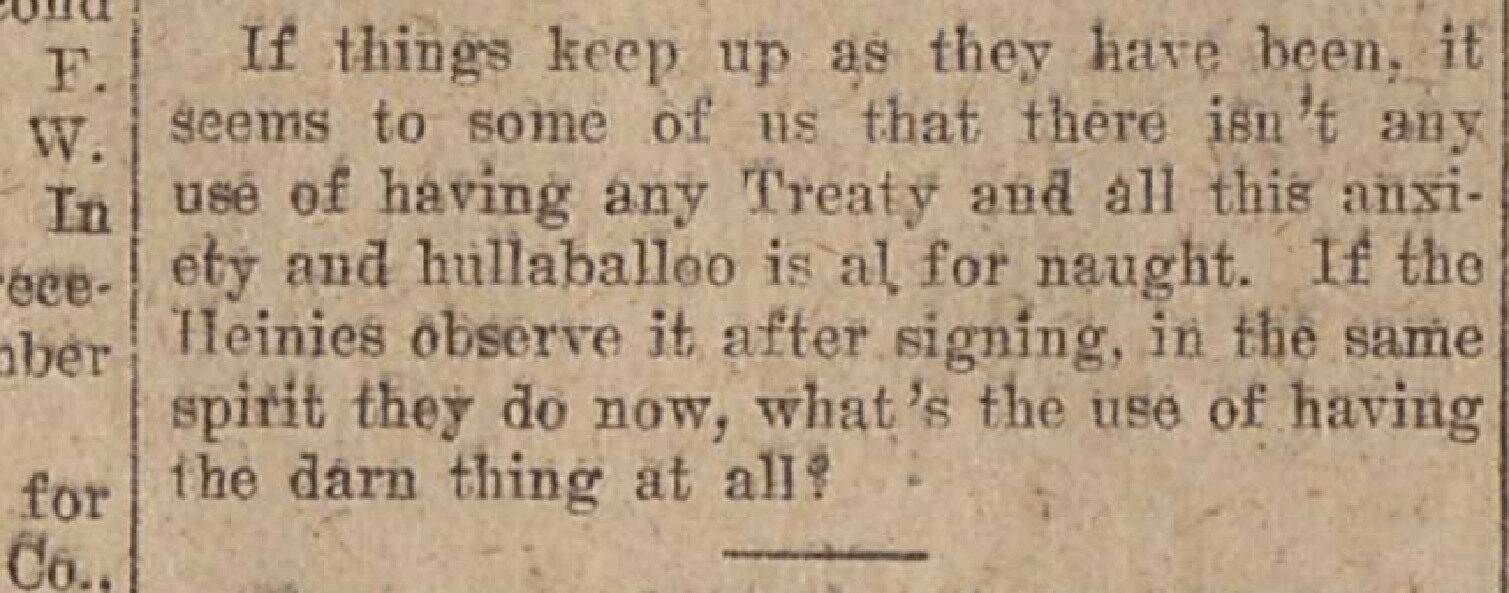

On another page of the same newspaper, an article contemplates the situation in Germany and the efficacy of the treaty:

The Amaroc News, 28 June 1919, Image © National WWI Museum at Liberty Memorial Archives. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

For more information about First World War Portal, including free trial access and price enquiries, please email us at info@amdigital.co.uk.

Recent posts

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.