'Of whiche londes & jles I schall speke more pleynly here after': The travels of Sir John Mandeville

As covid restrictions are eased and thoughts turn, at least here in Britain, to travelling abroad, my own thoughts have turned to our digital collection Medieval Travel Writing, and to a mysterious globetrotter, or yarn-spinner, or both, about whom so much is contested that even his existence is a matter of debate – Sir John Mandeville.

A representation of Sir John Mandeville, 1459, from Spencer Collection Ms. 037 at the New York Public Library.

The frontispiece of the 'Coventry Book of Mandeville'. Image © The Herbert: Coventry History Centre. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission.

In the prologue to his Travels (sometimes known as The Book of the World’s Marvels), over fifty copies of which, in five languages, are compiled in Medieval Travel Writing, Mandeville is clear about where he was from and the extraordinary collection of places he had been. In A. W. Pollard’s modernised English of 1900:

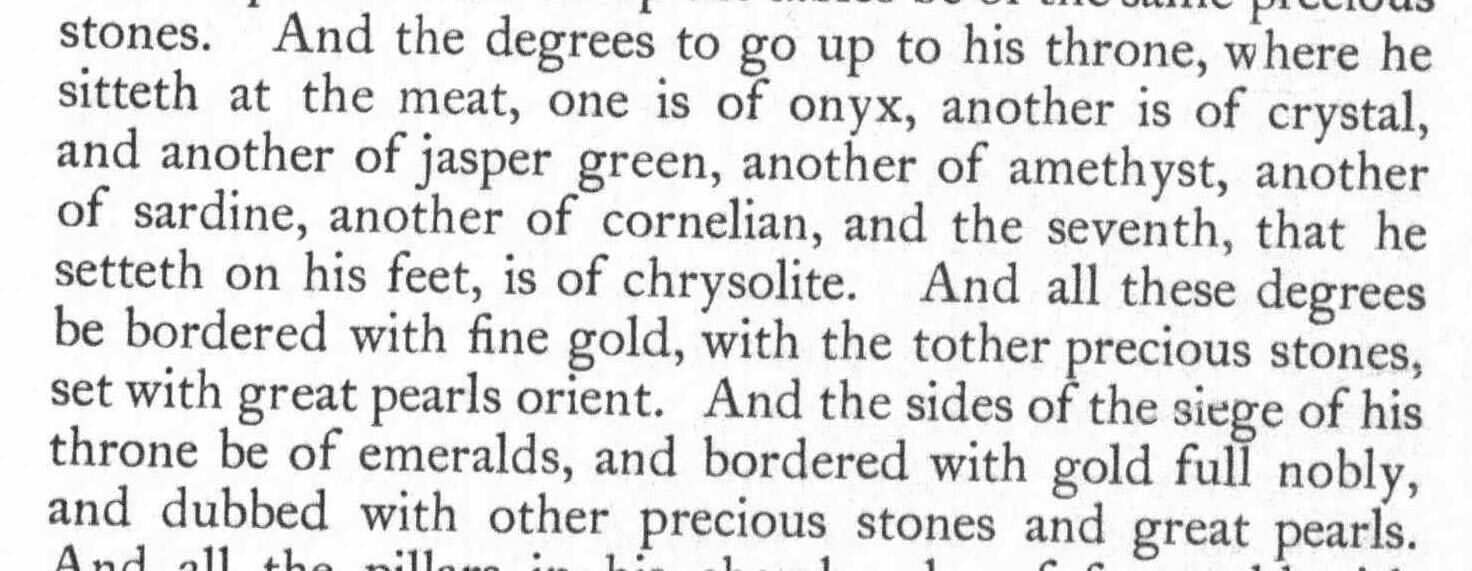

From Mandeville’s prologue in A. W. Pollard (ed.), 'The Travels of Sir John Mandeville' (London: Macmillan, 1900). Image © The British Library. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission.

But Mandeville’s account of these peregrinations is, by our standards, distinctly odd. He sets out his stall in his opening paragraphs, wherein he tells the reader that there are many ways to go from England to Constantinople; and then, via a digression about the extent of the Danube basin, arrives in that city, without actually saying what he did to get there himself.

As the book progresses, the details Mandeville gives of where he has been, passed from verifiable to fantastical – from the site of the relics of St Catherine at a monastery in Sinai, described by Giles Milton in his popular work on Sir John, The Riddle and the Knight, over 600 years later, to the fictitious palace of the equally fictitious Prester John, the Christian potentate beyond the seas who so excited the diplomats of the Middle Ages:

Mandeville's description of Prester John's throne room from Pollard. Image © The British Library. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission.

Accounts of people with horns, one eye and no mouth follow. What is going on here? Mandeville cannot have travelled to the realm of Prester John, but did he go to the places he describes which do exist? Did he even exist himself?

Scholars’ consensus (though Milton is an exception) seems to be that the work attributed to Mandeville was actually written by a physician from Liège, Jean de Bourgogne – though the main source for this is a Liège chronicler who states that he was the only person to whom Bourgogne revealed himself as Mandeville.

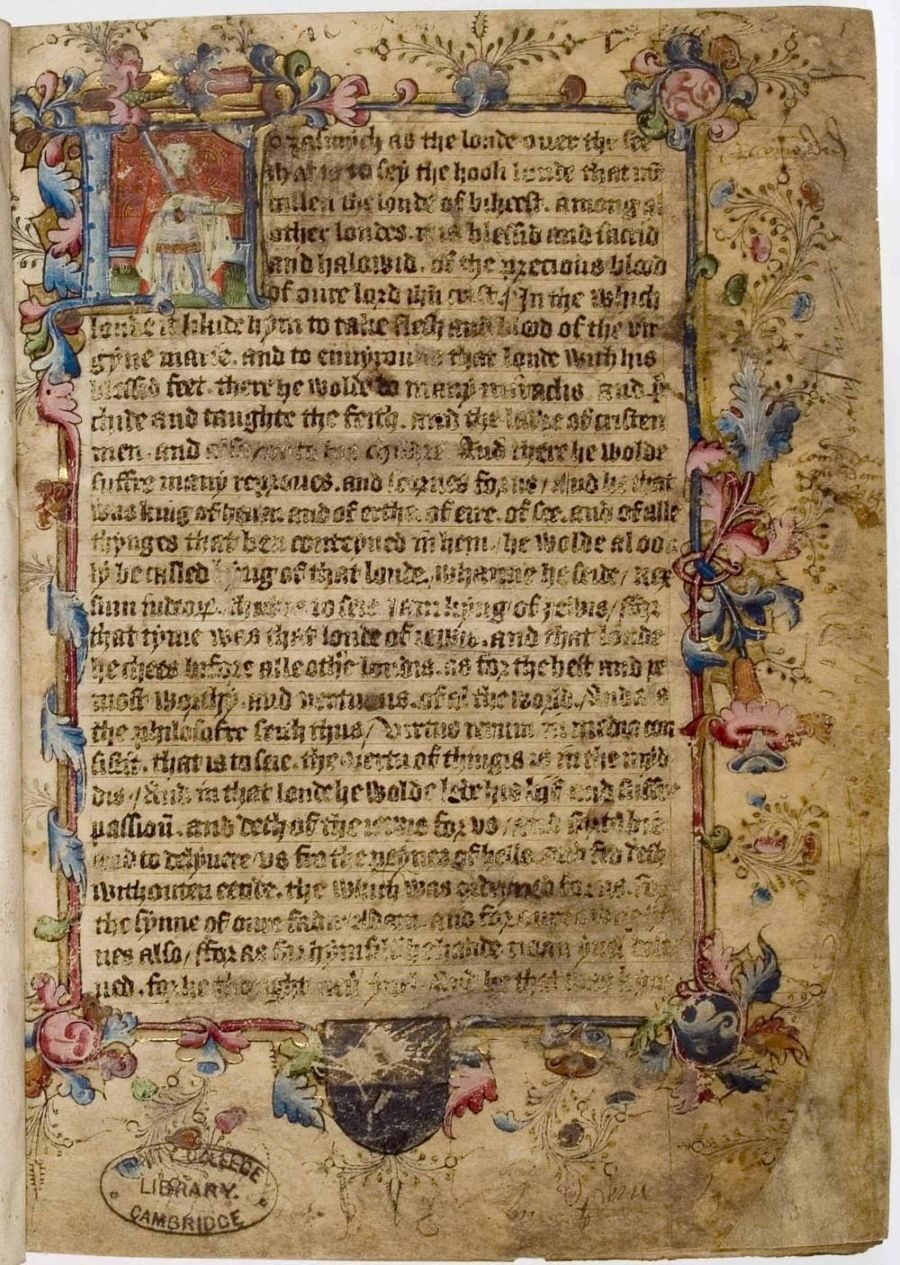

The first page of MS R.4.20, a Middle English copy of Mandeville from the early 15th century. Image © Trinity College, Cambridge. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission.

What is known beyond doubt is that copies of the Travels in French predate any in English and that various passages are clearly appropriated from other writers whose works feature in AM’s Medieval Travel Writing, including Odoric of Pordenone, Hayton of Armenia and John of Plano Carpini.

But, whatever the truth about Mandeville, his work does represent one of the very first attempts to discuss secular subjects in English prose, even if in translation, and is known to have influenced Christopher Columbus in his venture to reach the east by sailing west.

About the collection

Medieval Travel Writing is out now.

Recent posts

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.