The Empire Writes Back: ‘Christmas in its true aspect’

One of the many collections from AM’s microfilm catalogue which we’ve digitised – and also, we're confident in asserting, the best-named – is The Empire Writes Back. Taken from the British Library and published as part of Area Studies: India, this consists of books and periodicals on varied subjects, such as a treatise on infant marriage and a memoir of Joseph Salter, a Christian missionary among Asian sailors in London. However, most of the publications were written by Indian authors and published in India for a domestic audience, and the predominant topic is the travels of these Indians to Europe generally and Britain in particular.

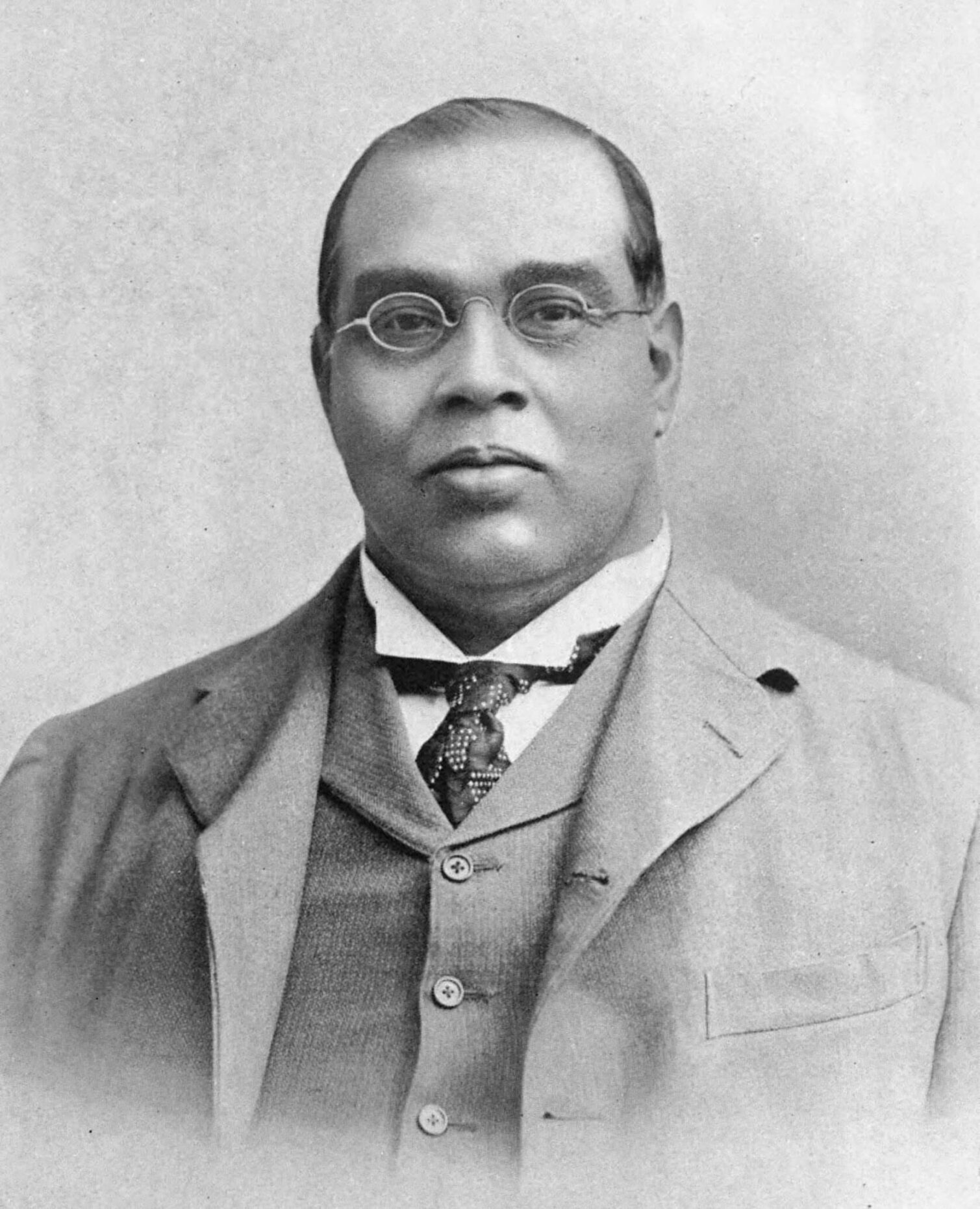

Romesh Chunder Dutt, from 'The Life and Work of Romesh Chunder Dutt, C.I.E.' (1911). From Wikimedia Commons.

By the mid-nineteenth century, there were about 40,000 Indian people in Britain. Most were sailors, of the type evangelised by Salter, but among them was a minority of students, artists and civil servants, some of whom would write about their experiences of a life that was both familiar, through second-hand exposure, to their affluent, English-reading audience, and deeply alien.

The Bengali novelist and translator Romesh Chunder Dutt published the letters he sent home to his brother as Three Years in Europe in 1873. He had spent Christmas 1868 in London, and noted the contrast of the deserted city to the colour and noise of celebrations in India:

"Unlike what we have at home on festive days, it is all quiet and still in the streets, shops and offices are all closed, and the whole town presents a sort of funereal appearance."

For, unlike Indians, Britons partied at home:

"But do you like to see Christmas in its true aspect? Go to the interior of one of the houses, and mark what passes on there. What with the joy and gladness of every member of the family now assembled together, what with the group of happy faces round a cheerful hearth, what with the roast beef and Christmas plum-pudding of old England, and what with the temptations under the mistletoe, Christmas is a jolly time indeed in England."

His mention of mistletoe is particularly interesting, since he doesn’t specify what the temptations were. (To eat it? To propagate from a cutting?) Could his readers, educated and probably anglophile, be presumed to know already? Or were the facts outrageous to the subjects of the queen-empress and so could not be stated plainly?

Queen's College, Oxford. By simononly. From Flickr via Wikimedia Commons.

Those Christmas revellers in Britain who couldn’t go home would not be stuck out in the (in Chunder Dutt’s words) ‘congealed’ rain if they were fortunate enough to be students of Queen’s College, Oxford, where they could enjoy the Boar’s-Head Gaudy. Samuel Satthianadhan, the son of the first Indian bishop, was at Cambridge in the 1880s, and in his book Four Years in an English University he dilated on some of the peculiarities of its great rival:

"On Christmas day, […] the dining hall is generally crowded with visitors. A trumpet blast proclaims the summons to dinner. Then two cooks, with white aprons and caps, appear, bearing aloft that all may behold it, a huge boar’s head with gilded tusks, having in its mouth a lemon, and the large pewter dish decorated with bay, holly, rosemary and banners."

As this splendid sight was displayed to the diners, one of the college fellows praised it in ‘The Boar’s-Head Song’, part-English, part-Latin.

But even if gilded heads are not your festive bag, spare a thought for poor T. N. Mukharji, sent by the Indian government to the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London in 1886. Journeying home through Europe, he found himself, on Christmas Day, on the wrong train in Bohemia. Ejected by the guard for non-payment of an excess fare, he approached the stationmaster of the lonely rural halt at which he had been deposited:

"He was so taken aback by the sudden appearance which my person and dress presented before his eyes that I feared he would run away[,] taking me for something […] expressly deputed from a hotter climate than Upper Egypt to join him and his friends in their Christmas carousals."

Fortunately our man was taken to a hotel, but not before having to rescue a drunkard passed out in the snow and in danger of freezing to death.

A seasonal Ústí nad Labem (German: Aussig), Czech Republic, where T. N. Mukharji spent Christmas 1886. By ŠJů. From Wikimedia Commons.

Christmas originated in the Middle East, but we in the West have a tendency to assume our customs – mistletoe, roast meats, icy stupor and all – are the norm. These letters offer a glimpse into three very different Christmases spent encountering European life for the first time.

Area Studies: India and other modules of AM Scholar are available now. For more information, including demo and price enquiries, please contact info@amdigital.co.uk.

Recent posts

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.