"Little difficulties will get to be great difficulties": Joel Palmer and the Office of Indian Affairs in the Oregon Territory, 1853-56

This post has been written by Sarah Cullen, PhD candidate of American Literature at Trinity College Dublin and is the third in a special series from members of the British Association for American Studies (BAAS) to support the second BAAS Digital Essay Competition, sponsored by AM. The winner will receive £500 and one year’s access to an AM primary source collection of their choice.

“Experience has taught us the white and red men cannot always live together in peace,” Joel Palmer informed leaders of the Chenook tribe at treaty negotiations, estimated to have taken place on Saturday, June 23rd, 1853: “When there are but few whites they can get along very well and not quarrel, but when there are a great many they will have difficulty. When they live together there will be difficulties; little difficulties will get to be great difficulties” (25).

If one quote were to sum up this the ‘Frontier Life’ collection, Palmer’s words above would be the most appropriate. The reality discovered in these correspondences, between Palmer, his fellow agents of Indian Affairs in the Oregon Territory and their business partners, highlights both the scaremongering, thievery, and violence the indigenous Oregon population suffered at the hands of the white settlers in the 1850s, and the steps taken by the Office for Indian Affairs to curb interaction between the two groups. This ultimately ensured that the white settlers were given the most fertile, desirable land, and could feel free from the threat of Indians. The intentions then, were to address “difficulties” that the white settlers created themselves.

Click to see the original document in Frontier Life

The collection focuses on letters and correspondence of Palmer (1810 – 1881), the superintendent of Indian affairs in the Oregon Territory, from 1853-57. Palmer was responsible for establishing many reservations, negotiating nine secession treaties from tribes in the surrounding areas. ‘Frontier Life’ has a cross-section of correspondence and other texts relating to Palmer’s career. They are composed mainly of correspondence to Palmer from his colleagues, from the years 1853-73, as well as his diary for 1854-1956, 1860- 1861, and 1871-74.

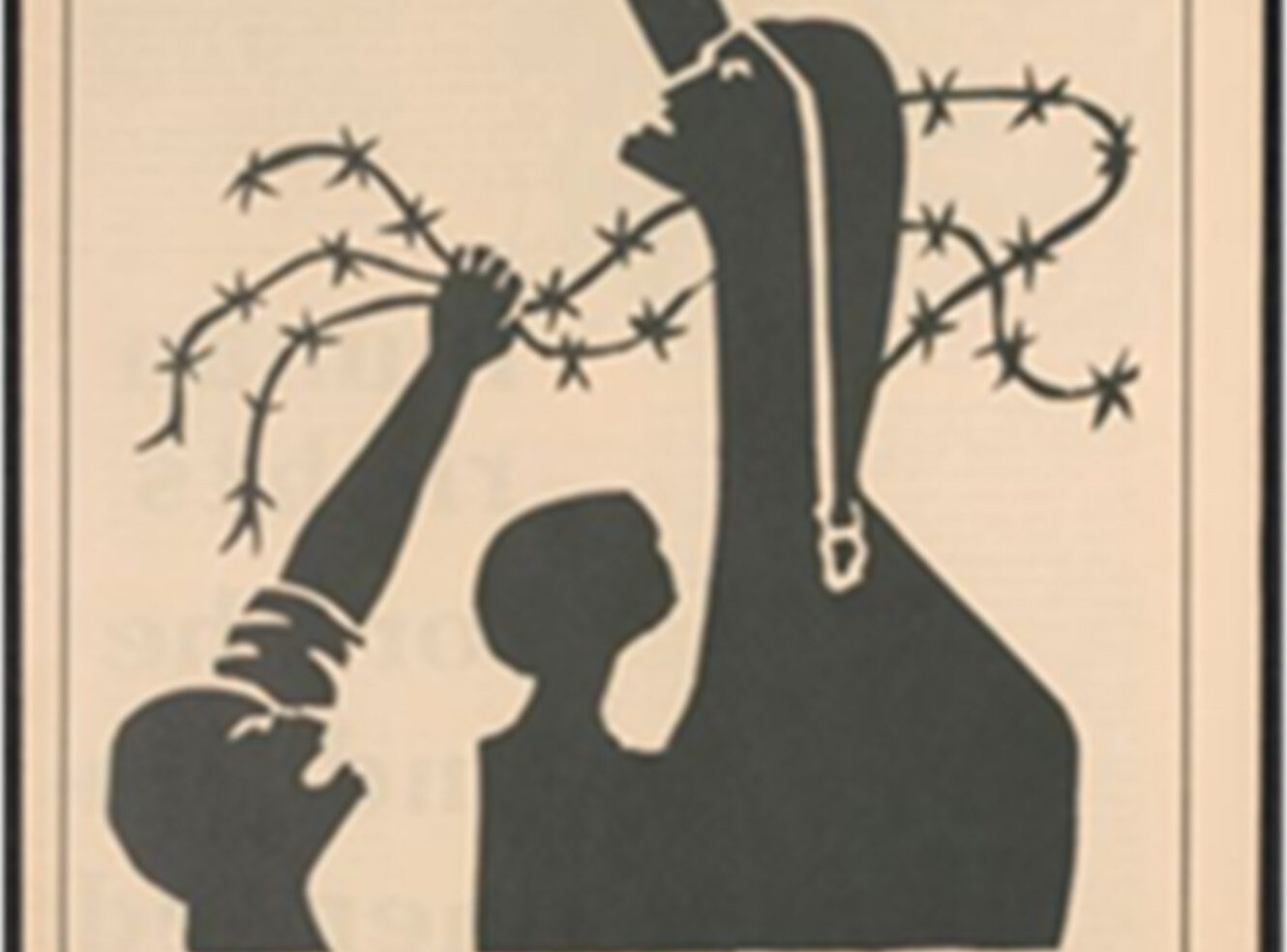

The letters address measures taken by the Office of Indian Affairs to remove agency from Oregon tribes, warning against providing alcohol to the Indians and the dangers of allowing them to join together in large groups, unsupervised. Another agent announces plans for restructuring the fishing activities of the indigenous populations along Rogue River. By hiring one “large seine and collecting the Indians at that riverland [sic]” he believed that he could “control them much better than I can as they are scattered the whole length of the District” (3). Meanwhile, the biggest operation set in motion was the establishment of the Grand Ronde reservation in which natives from Yamhill, Umpqua and Walla-Walla, amongst others, were gathered and interred from 1854. Considering the descriptions given of the Grand Ronde camp by Palmer’s secretary, Edward. R. Geary, to Lieutenant E. B. Stone, there is little surprise that parallels have been drawn between the Native American reservations and Nazi concentration camps. Geary’s missive to Stone instructs him, “to collect the Yamhill Band of Calipooia Indians at some suitable point […] [and] not permit any of the men to be absentwithout [sic] a written pass from you.“ As well as a daily roll call and punishment for anyone acting “refractory or insolent” such as confinement or the forfeiture of annuities, there were also meagre daily rations doled out: “one pound of flour to each adult and less in proportion to the children. If you find it necessary you may also issue a pound of beef to each adult daily” (7).

Click to see the original document in Frontier Life

Perhaps the starkest irony is that any justification for such inhuman treatment is undercut by Geary’s own qualification later on in the same letter. He warns, “It is v earnestly hoped that no one will be led by the excitement at present exhisting [sic] to do ant [sic] rash act of violence which may drive the peaceable Indians which otherwise they would not think of” (7-8). The white settlers were the danger, yet the Department of Indian Affairs were claiming to be acting in the interests of less intelligent peoples who would prove a danger if left to their own devices. As historian Ronald Takaki observes, white Americans had to have, “moral faith in themselves” and assure themselves they were innocent of brutality even while committing murder. This enabled them to practice self-deception in the removal of Indians, allowing them to “admire the Indian-killer and elevate hatred for the Indian into a morality[.]”

Palmer is considered an ambivalent historical figure. While his injunctions may have shielded the native populations from some of the white settlers’ most overt attacks, his actions forced the native populations into captivity, leading directly to their decimation. Any action undertaken by Palmer which was seen to favour the Indian was challenged by both the American press and legislators. Undercurrents of the lack of confidence in Palmer’s abilities as superintendent are seen in correspondence from General Joseph Lane. He urges Palmer to “see whether your Indian reserve is bounded as you suppose. […] Should it be found that the reserve alluded to embraces a much larger district of country than you suppose it mat [sic] operate against confirmation” (5). J. C. Avery, the founder of Corvallis in Oregon, is even more explicit in his disagreement. A proposed reservation “covers a large quantity of excellent agricultural that is not at present settled, as well as many harbours between San Francisco and the Columbia River which “many persons consider superior to any other on the Coast[.]” Permitting Indians to reside here would, according to Avery, not only “limit the population and wealth of this county,” but would also “diminish the value of all real estate of the county.” Avery concludes by noting that “much dissatisfaction is felt and expressed upon that subject by the people” (14).

Despite Palmer’s success at removing Indians, he was ejected from the post of superintendent in 1857 as he was considered to be acting favourably towards the native populations. By this time the population of the Grand Ronde was estimated to be almost twelve hundred. The years he held office were a self-fulfilling prophecy. Palmer and the Office for Indian Affairs in Oregon were adamant that not only “white and red men cannot always live together in peace,” but that the red men would never be given an opportunity to try.

~

Frontier Life is available now. For more information, including trial access and price enquiries, please contact info@amdigital.co.uk. For more details about the second BAAS Digital Essay Competition please click here.

Full access to this resource is restricted to authenticated institutions who have purchased a licence.

1. Coan, C. F. “The Adoption of the Reservation Policy in Pacific Northwest, 1853-1855” Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 23, 1 (Mar., 1922) p. 1.

2. Moya-Smith, Simon. “Ugly Precursor to Auschwitz: Hitler Said to Have Been Inspired by U.S. Indian Reservation System.” Indian Country Media Network. January 27, 2015.

3. Takaki, Ronald. Iron Cages: Race and Culture in Nineteenth-Century America. (London: Athlone P, 1980) p. 81.

4. Spores, Ronald. “Too Small a Place: The Removal of the Willamette Valley Indians, 1850-1856” American Indian Quarterly 17, 2 (1993) p. 189.

5. Joel Palmer and Isaac I. Stevens Biographies. Oregon Historical Quarterly 106, 3 The Isaac I. Stevens and Joel Palmer Treaties, 1855-2005 (Fall, 2005) p. 356.

6. Leavelle, Tracy Neal. "‘We Will Make It Our Own Place’": Agriculture and Adaptation at the Grand Ronde Reservation, 1856-1887 American Indian Quarterly 22, 4 (1998) p. 435.

Recent posts

Drawing on materials from Latin American Histories in the United States, this guest blog from Oliver Rosales, Bakersfield College, reveals the origins of the modern immigrant rights movement. Focusing on the amnesty campaigns of the late 1970s, we highlight how Chicano activists, grassroots publications, and cross-border solidarities shaped a pivotal era of Latinx political activism.

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.