Rivals on the Rocks: a scientific saga of the eighteenth-century stage

Tucked amongst the more familiar names of George Frederick Handel, Sarah Siddons and William Shakespeare, AM’s Eighteenth Century Drama: Censorship, Society and the Stage resource plays host to one scientist’s failed foray into the world of theatre: Sir George Mackenzie’s Helga; or, The Rival Minstrels.

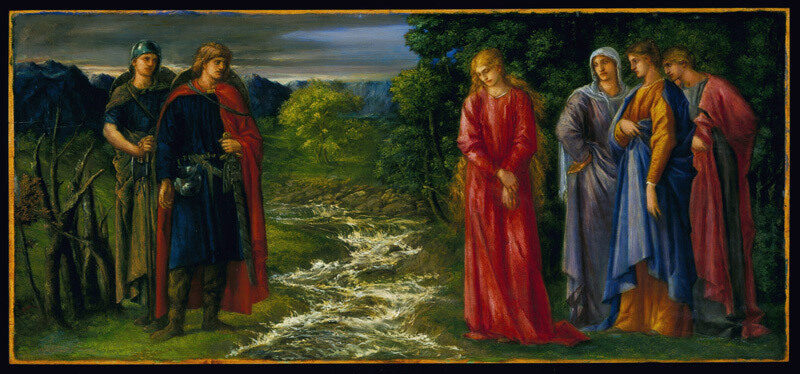

The Last Parting of Helga and Gunnlaug (Charles Fairfax Murray) 1880-1885. Image via: Wikimedia Commons

Based on the 13th-century Icelandic saga Gunnlaugs saga ormstungu, the story features two poets engaged in what amounts to a skaldic rap battle for the hand of the most beautiful woman in Iceland, otherwise known as Helga the Fair. Mackenzie’s play is more tragic melodrama than saga, and he departs from his source with great artistic licence. Borrowing from Shakespeare, he renames his hero ‘Edgar’ (a name popularised in tragic theatre by King Lear and its many adaptations) and drives his heroine into an Ophelia-like madness. The play’s climax features a duel between the two rivals and closes with the hapless Helga collapsing upon the body of her favoured lover.

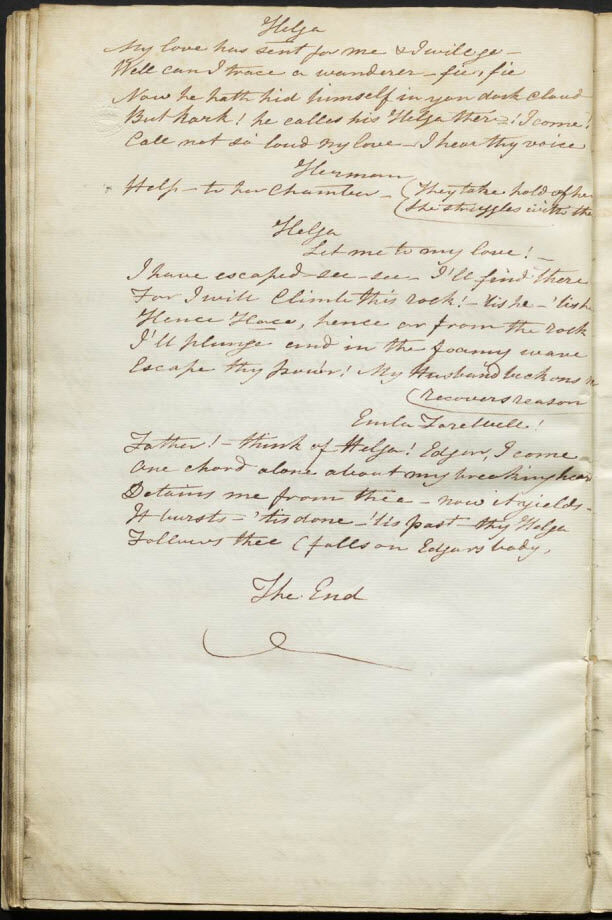

Edgar, I come – one chord alone about my breaking heart

Detains me from thee – now it yields – it bursts – ‘tis done – ‘tis past – thy Helga

Follows thee.

Helga; or, The Rival Minstrels, 1812 © The Huntington Library. Further reproduction prohibited without permission

Reaching for the dramatic heights of Lear’s “Break heart, prithee break”, Mackenzie’s offering was instead doused with scorn. Gales of laughter and mockery greeted the opening night and its run on the Edinburgh stage in the January of 1812 was embarrassingly brief.

The Rival Minstrels’ failure, however, had as much to do with a scientific scandal of the time as it did with Mackenzie’s arguably lacklustre creative ability. When he wasn’t moonlighting as a tragic playwright, Mackenzie’s interests lay in geology, and 1811 saw him fresh off the boat from a research trip to Iceland. The hot topic of the day was rock formation: Mackenzie favoured a volcanic theory, but a rival group known as ‘Neptunists’ fancied a more water-based solution to the question. Mackenzie attacked the Neptunists’ ideas in a publication entitled Travels in Iceland: an academic chemical burn which would sink his play’s hopes for success.

Sir Walter Scott, who had provided a prologue and epilogue for The Rival Minstrels and was deeply regretting it, wrote an embarrassed letter to a friend about the play’s poor reception, revealing that it was sediment, not sentiment, which had undermined Mackenzie’s work. The offended Neptunists, determined to avenge Mackenzie’s heated roast of their chemical theory, had shown up in full force to rain on his theatrical parade and swayed the opinion of audience and critics alike.

Icelandic sagas’ involvement with geological themes didn’t sink beneath the literary waves with Mackenzie’s failed enterprise: in his Journey to the Centre of the Earth Jules Verne made a saga manuscript the key to finding the volcanic tunnels which would lead his characters to (you guessed it) the centre of the earth. Unfortunately for Mackenzie, however, it’s fair to say that in this particular Icelandic venture it was the chemical rivals and not the poets who held the stage and won the day.

For more information about Eighteenth Century Drama, including booking a demo and price enquiries, please email us at info@amdigital.co.uk.

Recent posts

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.