Back to Fortress Singapore: A First-Hand Account

Our latest resource Foreign Office Files for Japan, Japanese Imperialism and the War in the Pacific 1931-1945, released this week, documents a turbulent time in Anglo-Japanese diplomatic relations.

Singapore, the epitome of British colonial rule with its grand government buildings and famous hotels, was also the British military stronghold in the East. Established as a defensive Naval base following WW1 it was bolstered at great expense as a reaction to Japanese expansion during the

Britain surrender to the Japanese, February 1942.

This report from 1945 written by Esler Dening, Chief Political Adviser to the Supreme Allied Commander, details his trip to Singapore, just eight days after the formal surrender of Japan. The document paints a picture of the conditions in Singapore and offers interesting insights into how it was viewed by a member of the British government.

Arriving in Singapore on the 10th September, two days before the official surrender ceremony was to be held on the 12th, he describes cruising along the coast of Sumatra, still in Japanese hands, and coming ashore in “a boat paddled by wooden boards.”

Extract of

Extract of In the

He paints a vivid picture of the surrender ceremony, recounting “a brave showing of the Royal Navy and Marine band’, the Supreme Commander arriving

Of the rife starvation and destruction on the island, he notes after an exchange with a starving Chinese family, “I think we were wrong in suppressing Japanese currency from the word go when we were not yet employing any numbers and our own currency had not yet got into circulation”.

Describing his trip to Changi Jail, he revealed “I came away feeling it was almost unbelievable that men (and women) had endured so much and preserved such a marvellous spirit” although, in a telling show of prevailing colonial attitude he also notes “We were shown the cell … Before the

Despite this perseverance of spirit and the cheers for the Supreme Commander, that Britain had let Singapore fall had left its authority in Singapore and other occupied colonial territories shaken: a fact that would play some part in the decline of the empire over the following decades.

This report will be open access for 30 days. Read it here.

Japanese Imperialism and the War in the Pacific, 1931-1945, the first section of Foreign Office Files for Japan, 1919-1952 is out now. Read more here. This resource is part of Archives Direct, sources taken from The National Archives, UK.

Recent posts

Foreign Office, Consulate and Legation Files, China: 1830-1939 contains a huge variety of material touching on life in China through the eyes of the British representatives stationed there. Nick Jackson, Senior Editor at AM, looks at an example from this wealth of content, one diplomat’s exploration of Chinese family relationships and how this narrative presented them to a British audience.

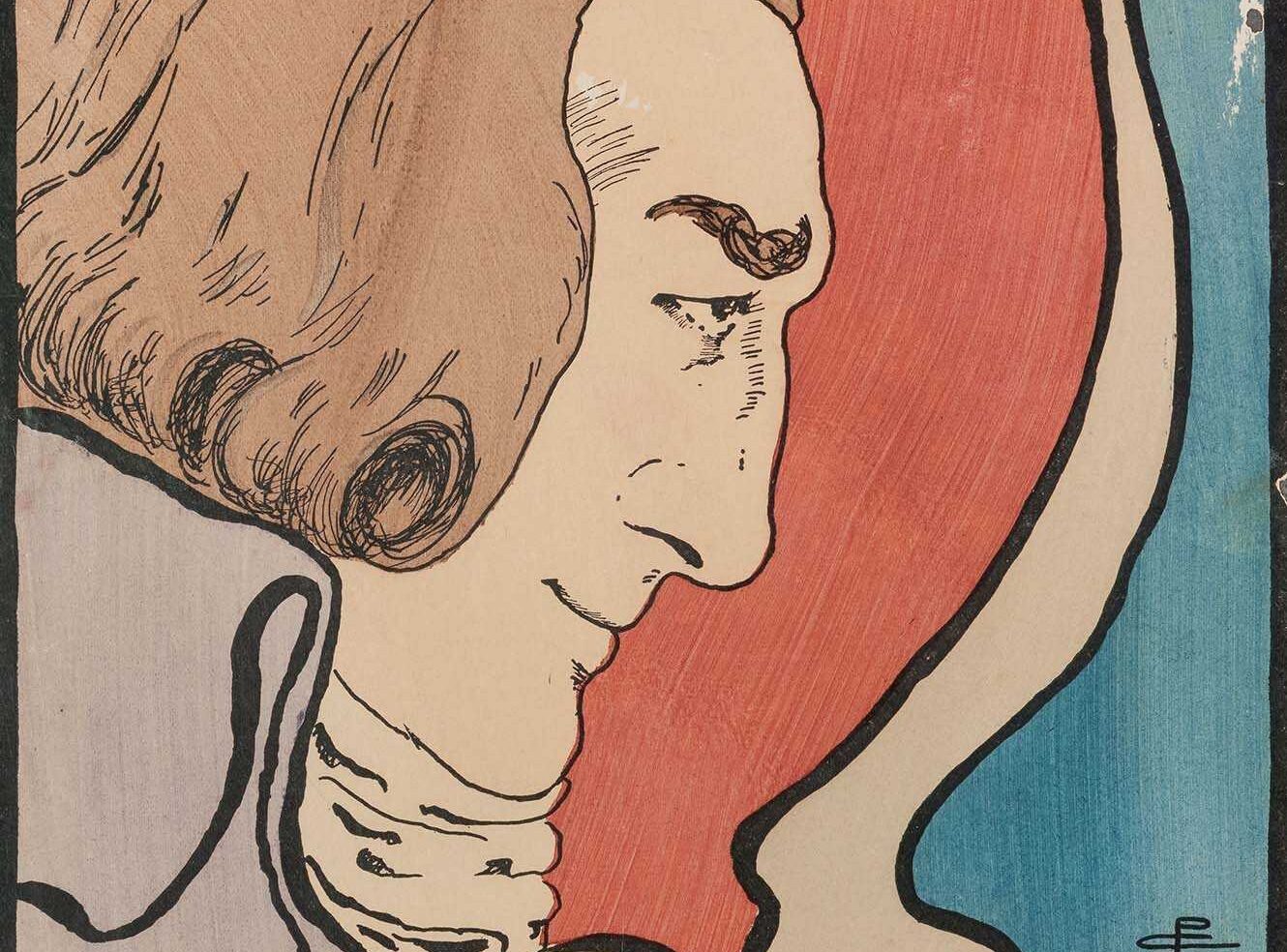

The Nineteenth Century Stage is a rich resource exploring the theatrical celebrities, artistry, and changing social roles of the era. It highlights Pamela Colman Smith, known for her Rider-Waite tarot illustrations and theatre work, whose influence shaped Victorian theatre. Despite being overlooked, her life and impact are vividly captured through striking art and intimate collections within this valuable resource.