If a woman smiles, her dress must also smile: 1930s fashion in Interwar Culture

The 1930s are calling, the fashion is French, and the word du jour is "glamour". That's right, Interwar Culture: 1930-1939 has been published, and to celebrate we'd like to show off some of the beautiful 1930s fashion you'll find within. To that end, there are two designers you probably don't know (and should): Madeleine Vionnet and Lucien Lelong.

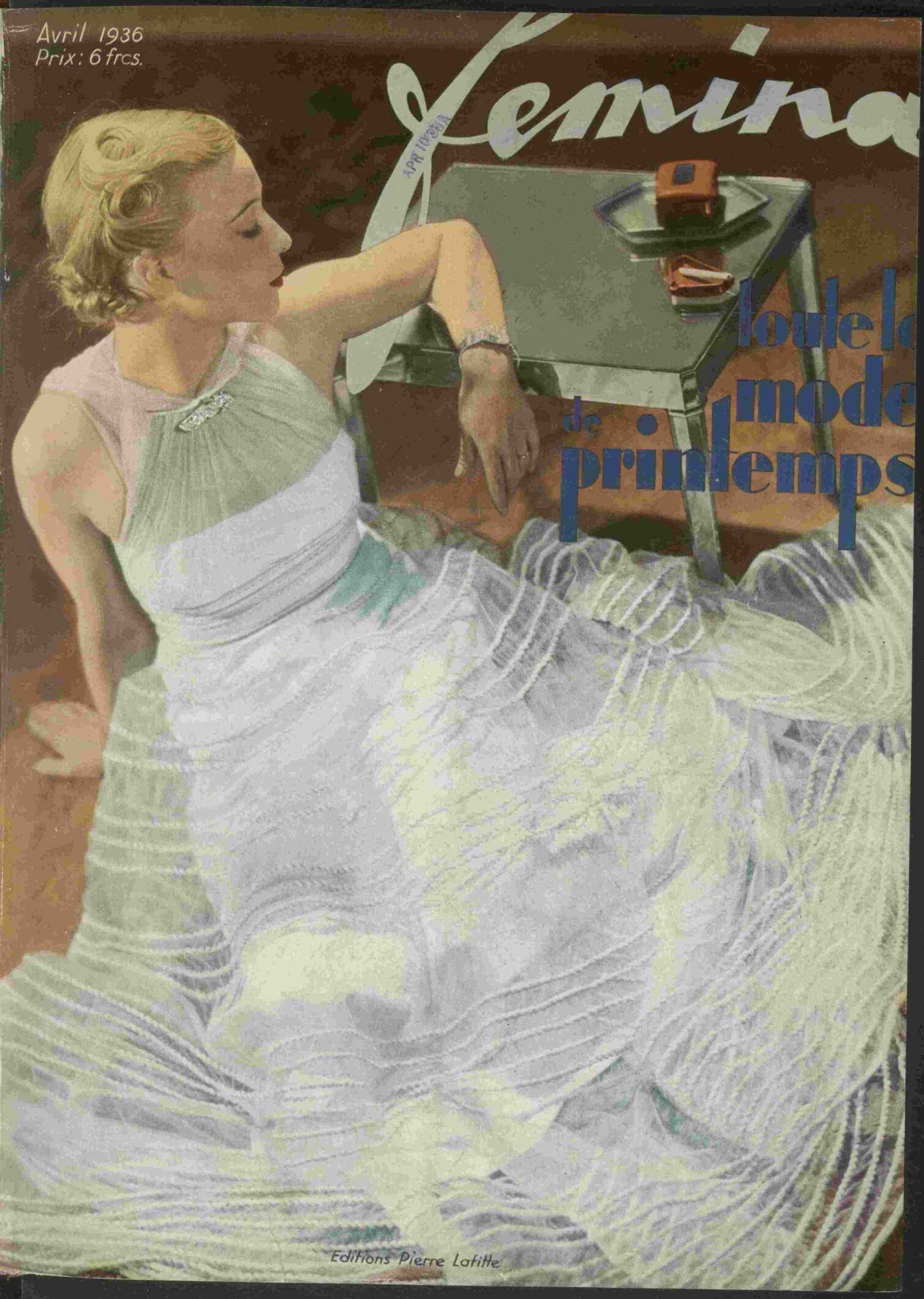

Femina, April 1936

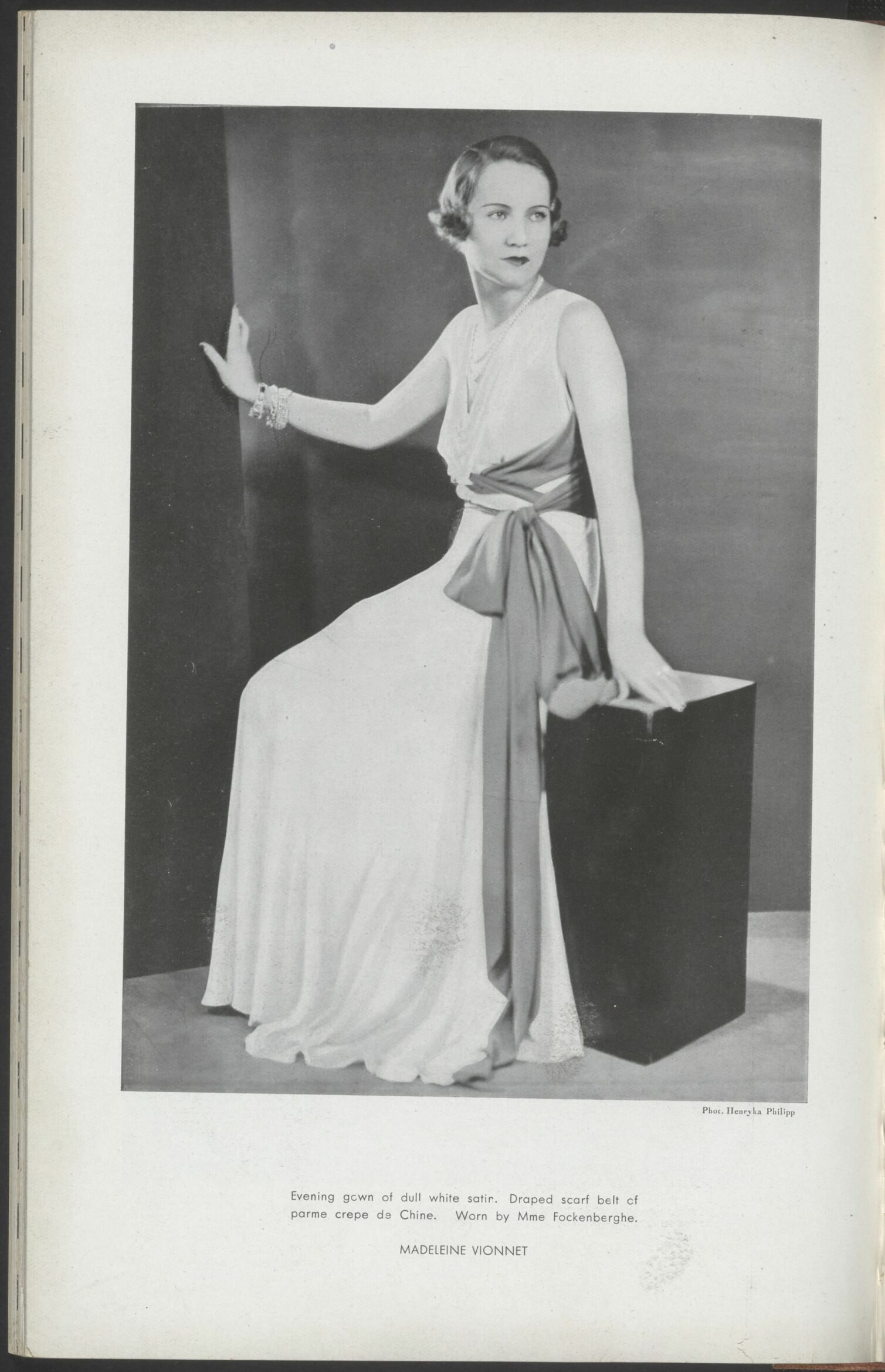

Madeleine Vionnet pioneered the bias cut dress in the 1920s and the technique rose to red carpet fame in the thirties. Vionnet turned away from the garçonne look of the flappers to a more conventionally feminine glamour that defined the fashion of the decade and changed haute couture forever. Her customers included European aristocracy and wealthy American socialites like Baroness Robert de Rothschild and Mona Von Bismarck who exerted huge influence.

Taste is the feeling that permits one to tell the difference between what is beautiful and what is merely spectacular.

Art, Goût, Beauté, Volume 13 - Issue 151 - Mar 1933

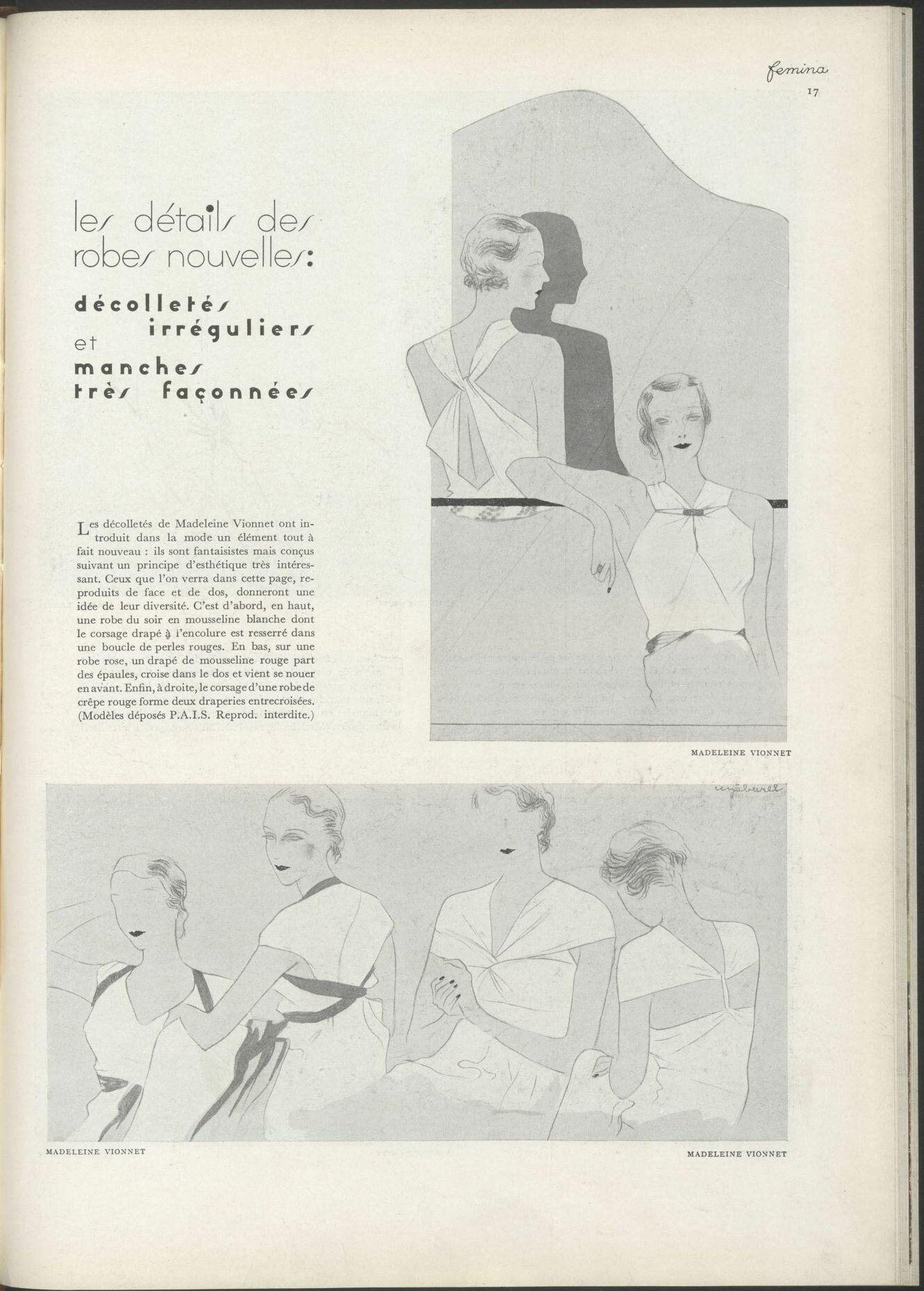

The bias-cut technique cut the fabric against the grain at a 45-degree angle, resulting in a draped silhouette that clung to woman’s figure but retained flowing movement. Vionnet encouraged women to go without corsets or stays, preferring a natural figure beneath her designs. Often the draperies of the dresses were not sewn down and her clients were taught how to drape the dresses once they were wearing them to achieve the desired effect. Her work encapsulated the Art Deco obsession with movement and her geometric precision called upon Cubist influences.

Femina, les détails des rodes nouvelles

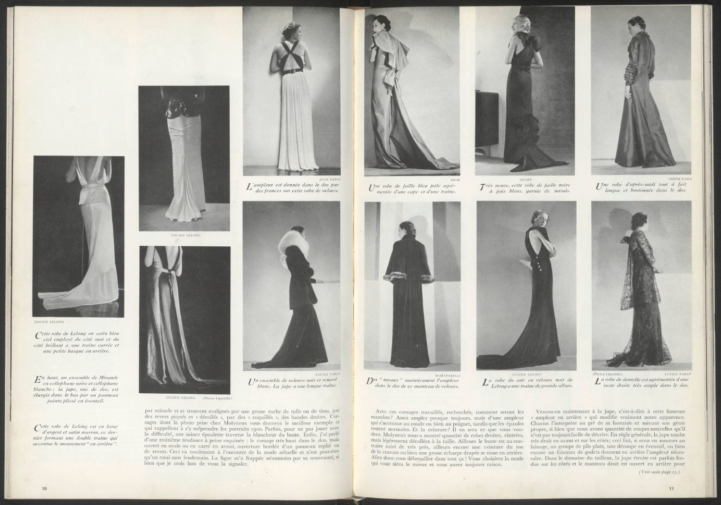

Similarly, Lucien Lelong was an eminent couturier in Paris in the interwar period. He was not a designer himself, however, instead working in collaboration with a team of designers to create collections for the house of Lelong, which had been A.E. Lelong when operated by his parents, Arthur Camille Joseph Lelong and Éléonore Marie Lambelet. Balmain, Dior and Givenchy all worked under Lelong in his fashion house before establishing their own houses.

Neither Balmain nor I will ever forget that in spite of wartime restrictions and the constant fear of closing, Lelong taught us our profession.

Femina, Oct 1934

There are conflicting rumours about his sexuality, nonetheless, Lelong married three times and had a daughter with his first wife. The lipstick Nicole Pink was named for his daughter. His second wife was a first cousin of Tsar Nicholas II who had survived the Russian revolution and emigrated to Paris; Princess Natalia Pavlovna Paley married Lelong in 1927 and their union lasted ten years. It was said to be a white marriage without romantic intimacy, but it benefitted Lelong’s career enormously. Princess Natalia was a sought-after model by high-profile photographers like Cecil Beaton, and often set fashion trends that strengthened her husband’s reputation.

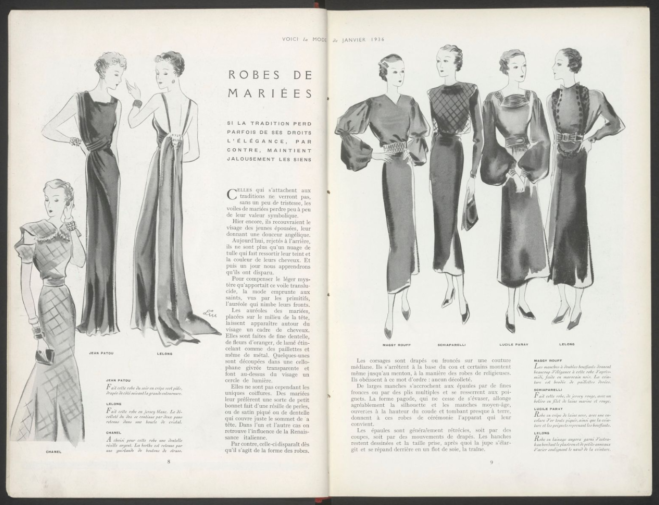

Voici la Mode; Art, Goût, Beauté, Jan 1936

Directly in competition with Coco Chanel in both fashion and politics, Lelong was firmly against the spread of Nazism in Paris. When the Germans invaded in May 1940, he was President of the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture, responsible for negotiating with the Nazis on behalf of the couturiers of Paris. The Nazis forcibly moved the entire archive of haute couture to Germany, planning on forcing the haute couture industry out of Paris and into the “fatherland” in an effort to make Germany the heart of European fashion.

Lelong persuaded them that the industry was dependent on many independent experts of niche craftsmanship; these skills took decades to attain and were virtually unteachable, making it impossible to move fashion out of Paris. The Nazis conceded and returned the archive. He was also able to negotiate the original 80% conscription into the Nazi labour force down to 5%.

The fashion of the 1930s is a microcosm of the decade’s extremes; the pioneering techniques and glamour of the red carpet thrust aside by the roiling political turmoil that erupted into World War Two. Interwar Culture offers a rare window into the fleeting but impactful trends that echoed the fast-paced nature of change, both socioeconomically and politically.

About the author

Eleanor Cambridge is an Assistant Editor at AM.

About the collection

Interwar Culture: 1930s is out now.

Recent posts

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.