"I do not like Pink Pills and spam"

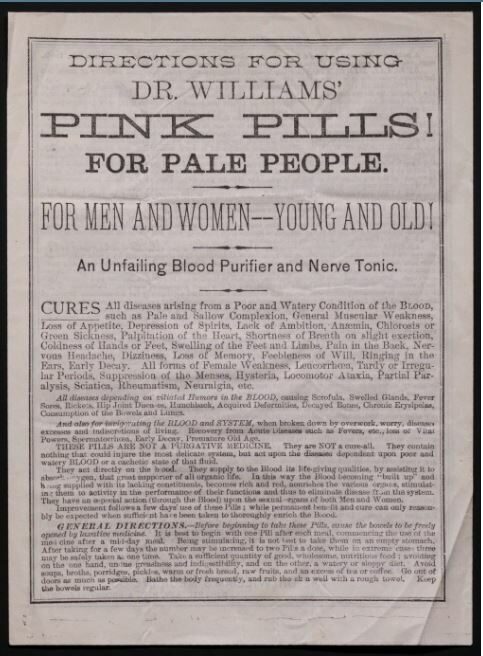

“Pink Pills for Pale People!” is the excited announcement from a leaflet that can be found in Popular Medicine in America 1800-1900.

If like me, you’re wondering whether the pink pills make people pale, or pale people pink, or perhaps that this much alliterative pinkness is beyond the pale...well, you might be right.

These pink pills (actually a ‘blood purifier and nerve tonic’, you will be dubiously relieved to hear) are just one of the many advertisements to be found in the nineteenth-century pantheon of popular tonics and remedies which range from the bizarre and ridiculously hilarious to some which hit a little too close to home.

Dr Williams’ Pink Pills for Pale People!, c. 1890-1899, © The Library Company of Philadelphia. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission.

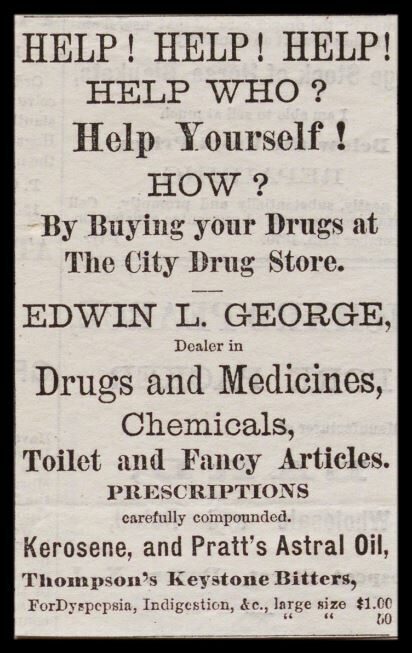

The collection presents an enthralling - and at times disturbing - insight into the targeted medicinal advertising of the time. For every prosaic druggist's advertisement announcing its name and place of business, there is another that goes the extra mile to grab its audience’s attention. Maybe it’s not always in the best ways, but in the advertising game, any attention is good attention, right?

This is certainly the approach of druggist Edwin L. George, who comes up with an alarmist promotion of their premises. The self-help-style slogan is a nice touch, but not enough to make up for the mini heart attack the first line might induce in innocent passers-by. I confess I am drawn in by the promise of ‘Fancy Articles’, however, so perhaps they’re onto something...

Edwin L. George, 12 Aug 1871, © The Library Company of Philadelphia. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission.

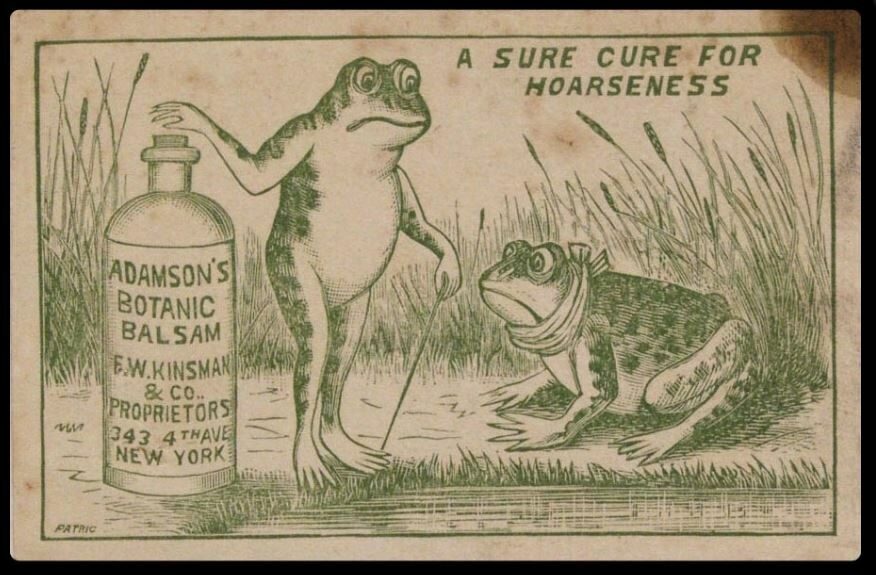

Meanwhile, one can only assume that the purveyors of Adamson’s Botanic Balsam were capitalising on the idea of ‘having a frog in one’s throat’, but as this glum frog’s rather dapper and scarf-like bandage suggests, there does appear to be some confusion over the location of both the hoarseness and the frogs themselves (is the frog’s throat hoarse? Is the throat a frog? No, me neither).

Adamson's Botanic Balsam, c.1870-1900, © The Library Company of Philadelphia. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission.

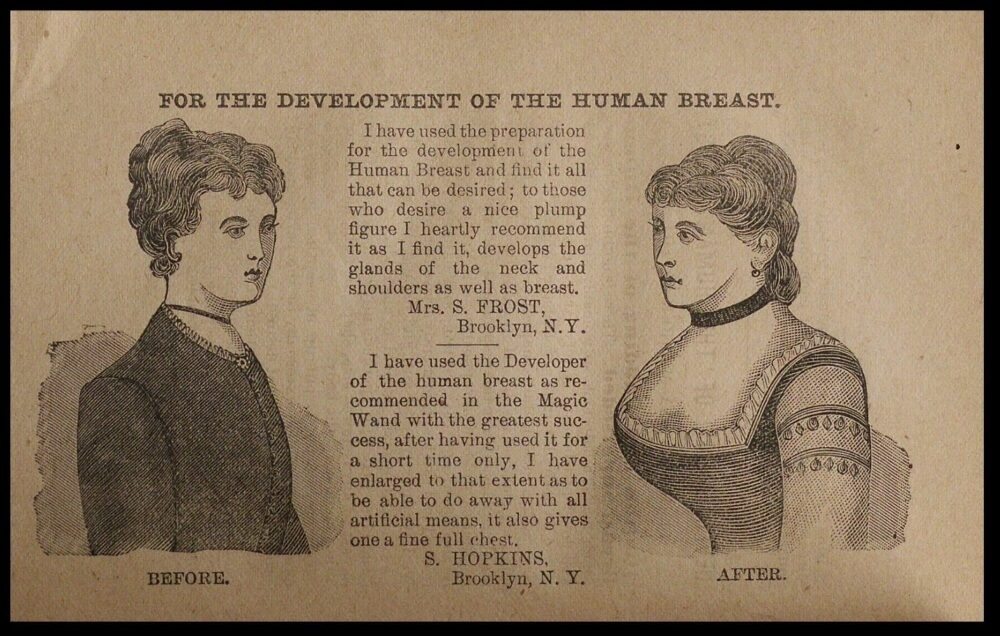

Humorous though they are, there are more sombre observations to be drawn from some of the advertisements. The modern battle with unrealistic and damaging beauty standards is, demonstrably, one that has been ongoing for centuries.

The Magic Wand and Medical Guide, of which the collection has two editions, contains “curious and marvellous disclosures” on topics ranging from courtship advice to preventing “an increase of family” and “the prevention and cure of all private diseases”. In all, it seems like the Cosmopolitan of its time - and in fact, The Cosmopolitan was first published a mere twenty years after this particular compendium.

One of its more startling offerings is in its 1889 edition, which features a “preparation for the development of the human breast”. One review claims joyfully that it has “develop[ed]” the glands in her neck and shoulders in addition to her breasts, and seems in no way deterred by the potential medical implications of this body-wide inflammation.

It’s a reminder that anxiety about our appearances, as much as our health, has been a preoccupation for generations, and that the two are often conflated - particularly in advertising - with potentially harmful effects. The documents of Popular Medicine in America 1800-1900 hold up a fascinating mirror to modern experience - and perhaps the reflection is a little too recognisable for comfort.

Magic Wand and Medical Guide, 1889, © The Library Company of Philadelphia. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission.

About the collection

Popular Medicine in America 1800-1900 is out now.

Recent posts

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.