Domestic science: Revolutionising the salad

When I first started working on the Food & Drink in History resource, I immediately became obsessed with molded jelly salads.

This food fashion fascinates me, so when I was invited to give a paper at the International Conference on Food Studies hosted by the London Centre for Interdisciplinary Research, I leapt at the chance to dig deeper.

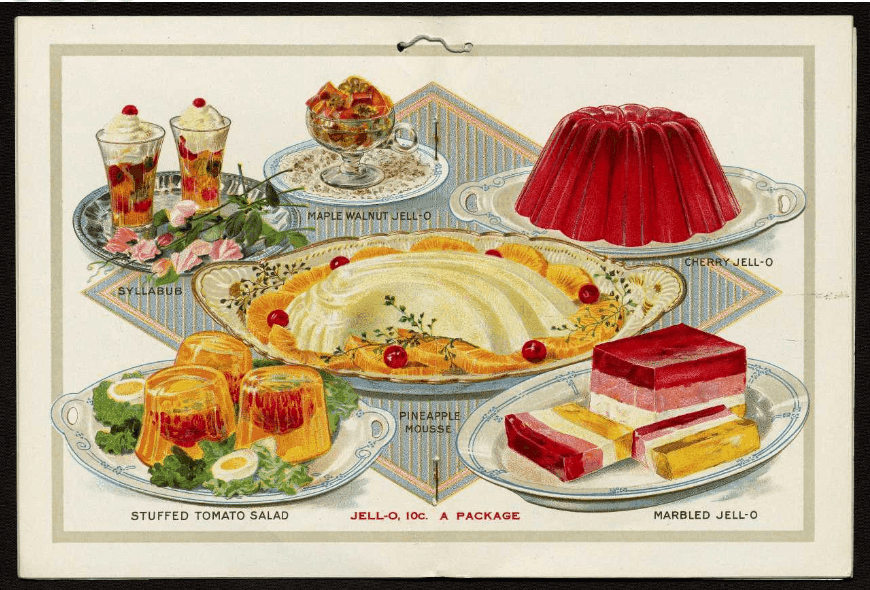

Jell-O, n.d., © Content compilation © 2020, by The New York Academy of Medicine. All rights reserved.

As it turns out, there are numerous reasons why molded salads became so popular – the pure foods movement (jelly is so clean!), technology (invention of instant gelatine), successful marketing (the first molded salad won a Knox magazine competition) – but the one that I found most compelling was the influence of the domestic science movement.

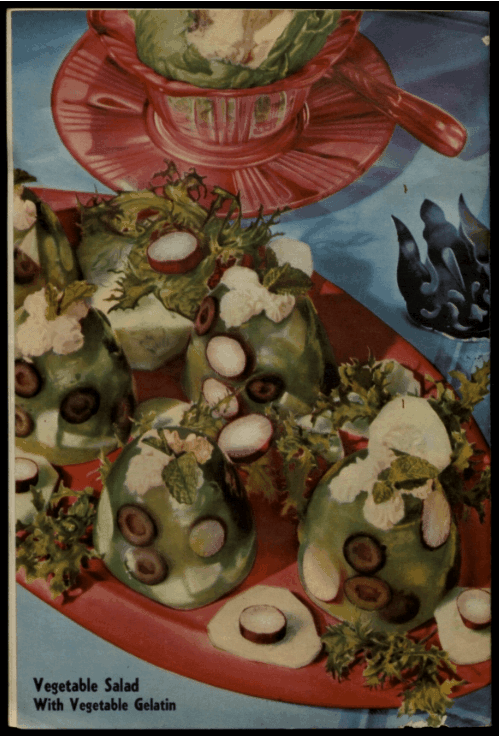

The molded salad exploded onto the culinary scene in the early 1900s and grew in popularity throughout the early-mid twentieth century. Part of the recipe’s appeal was its versatility; a molded salad could contain anything from meat, veggies, nuts, cottage cheese, and eggs, to marshmallows and fruit – whatever is in your pantry.

Flavourless gelatine and fruit jellos were used, in combination with juices such as tomato, cranberry and sweet pickle. These mixes would be poured into moulds and turned out for family dinners and social events often served with lashings of mayonnaise.

Royal Aspic Movie Recipes, 1934, © Material sourced from The University of Michigan.

Though salad was generally termed as mixed greens served with a dressing, the late nineteenth-century domestic science movement was influential in creating the right environment for the jellied innovation. Domestic science was about applying scientific principles to cooking, making it more efficient and effective.

Cooking schools sprang up across the US to teach this revolutionised approach, complete with famous practitioners like Fannie Farmer and Sarah Rorer. The salad came under particular scrutiny, with an emphasis on bringing salads under control; as Laura Shapiro in her book Perfection Salad notes, it was essential that salads were innovative, neat and dainty:

the tidiest and most thorough way to package a salad was to mold it in gelatin.

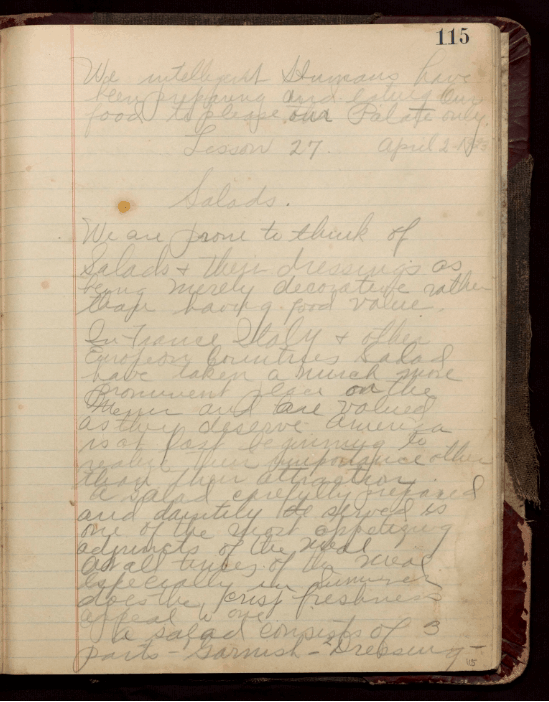

Shapiro also states that "Cooking school cookery emphasised every aspect of food except the notion of taste” and that salad was viewed as a “nutritional frill” and “a kind of non-food” (Shapiro, 2009, p94). We can see evidence for Shapiro’s conclusions in the Cooking Class notebook of Alice E. Buentin, 1922-1923, featured in Food & Drink in History.

Cooking class notebook of Alice E. Buentin, 1922-1923, © Material sourced from the University of Michigan.

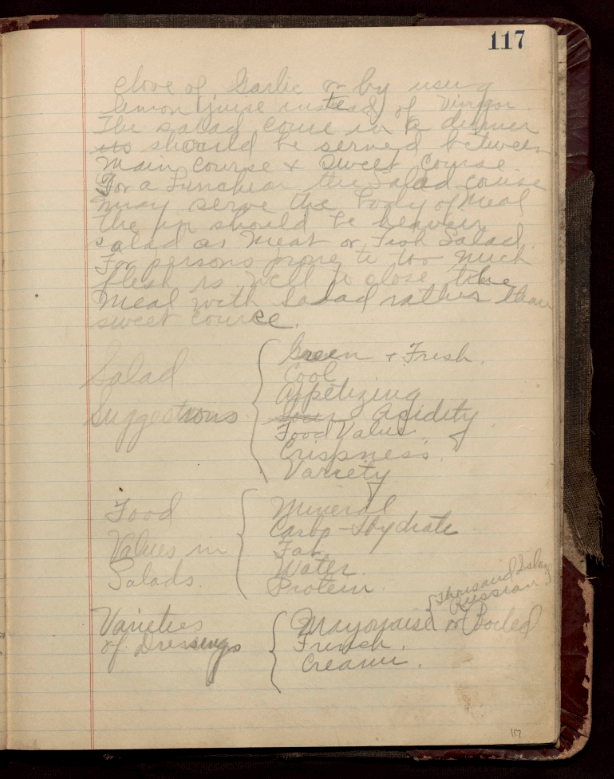

Buentin attends a lesson on salads and her first note is quite illuminating: “We are prone to think of salads & their dressings as being merely decorative rather than having food value.” This is supportive of Shapiro’s argument that the taste of salads is unimportant. Conversely, this cooking school is keen to convince their student of salad’s ‘food value’, though that value is largely measured in nutrition over taste.

She does highlight the ‘freshness’ of salad as appealing, supported by the accompanying recipes for Mint Salad. It contains mint, celery, green peppers and pecans in flavourless gelatine, to be served with mayonnaise dressing.

Cooking class notebook of Alice E. Buentin, 1922-1923, © Material sourced from the University of Michigan.

There is so much more to unpack in the history of molded salads that sheds light on the social history of America in this period. What Alice Buentin & Laura Shapiro show us is that the home cooks of the early twentieth century showed off their domestic science credentials by taking advantage of convenient and family-friendly instant gelatines to produce nutritional dishes that showcase control and innovation.

However, they may have cared very little about how it tasted – which could explain some of the weird and wonderful combinations!

About the collection

Food & Drink in History is out now.

Recent posts

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.