Defending Vera: Troops came to the defence of the forces’ sweetheart after attacks from Parliament (1944)

Vera Lynn is celebrated worldwide for her accomplishments in popular music throughout World War Two. Also known as the ‘Forces’ Sweetheart,’ Lynn sang to the British troops at home and abroad from 1939-1945 and is best remembered for her romantic ballads – including ‘We’ll Meet Again’ and ‘The White Cliffs of Dover.’

While these wartime achievements eventually crowned Lynn a national treasure to the United Kingdom, in 1944 the sentimental singer came under fire from members of the British Parliament, who objected to her slushy-song lyrics and expressive delivery. In a House of Commons sitting on 7 March 1944, Earl Winterton compared Lynn’s crooning to the ‘caterwauling of an inebriated cockatoo,’ objecting to her songs on the grounds that they would not have a ‘good effect on the troops.’

Documents from AM's Service Newspapers of World War Two, however, reveal that British troops from around the world quickly came to the defence of Lynn – citing her instrumental role in cheering them up and renewing their memory of home. While praise of Lynn was by no means universal, many troops took the time – mid-war – to write into their local service papers, with the express wish of defending Lynn and her so-called ‘slush.’ Gunner A. E. Buckeridge, for example, wrote to Union Jack (Italy/Western Italy edition) by 16 March 1944, urging Early Winterton to ‘concentrate his energy and ability on more important issues.’1

Union Jack (Italy/Western Italy edition), no. 112, 16 Mar 1944, © Material sourced from The British Library

Frank Owen, the publisher of the South East Asia Command (SEAC), thanked Lynn for her efforts, writing on 28 March 1944: ‘Bless you, Vera Lynn, you got on the abiding homesickness of the solider, and if you sometimes made him sad, you also renewed his memory of kindly things.’2

Similarly, in May 1944, L. A. C. Ball, a member of the RAF in India, wrote into SEAC to comment on a recent Lynn concert at a nearby hospital. He stated: ‘If only Lord Winterton could have been there, and heard the cheering and whistling for encores every time Vera tried to leave the platform, he would have been forced to change his mind about female crooners and the morale of the troops.’3 He continued: ‘I say emphatically that the morale of the troops went up 100 per cent after hearing Vera sing.’4

SEAC: The Daily Newspaper of South East Asia Comma..., 10 May 1944, © Material sourced from The British Library

While an overwhelming majority backed Lynn’s efforts, some listeners took the time to write into their local papers and express agreement with Earl Winterton’s statements. C. Pearson, from Sowerby Bridge, for example, claimed of crooners: ‘There isn’t a voice in the whole bunch put together.’5 Still, others claimed that Lynn’s effect on morale could ‘surely be regarded as exactly nil.’6

Regardless of one’s stance on sentiment, these service papers – coupled with the reports from Parliament – demonstrate that celebrities and popular music became matters of national concern throughout World War Two. Far from being the fascination of a gossiping periphery, the quality of a nation’s popular culture could be viewed as part and parcel to winning the war.

About the author

Clare V. Church (she/her) is a writer, researcher, and editor, specializing in themes of gender, media history, and collective memory. Originally from Canada, she is currently based in Aberystwyth, United Kingdom, where she is completing her Ph.D. in History and Welsh History.

About the collection

Service Newspapers of World War Two is out now.

Collection information

References

1 ‘The Fighting Man’s Platform’, Union Jack (Italy/Western Italy edition), 16 March 1944, p. 2.

2 ‘People’, SEAC: The Daily Newspaper of South East Asia Command, 28 March 1944, p. 3.

3 ‘Thanks, Vera’, SEAC: The Daily Newspaper of South East Asia Command, 10 May 1944, p. 2.

4 Ibid, p. 2.

5 People’, SEAC: The Daily Newspaper of South East Asia Command, 28 March 1944, p. 3.

6 ‘Good Morning…’, SEAC: The Daily Newspaper of South East Asia Command, 11 March 1944, p. 1.

Recent posts

Foreign Office, Consulate and Legation Files, China: 1830-1939 contains a huge variety of material touching on life in China through the eyes of the British representatives stationed there. Nick Jackson, Senior Editor at AM, looks at an example from this wealth of content, one diplomat’s exploration of Chinese family relationships and how this narrative presented them to a British audience.

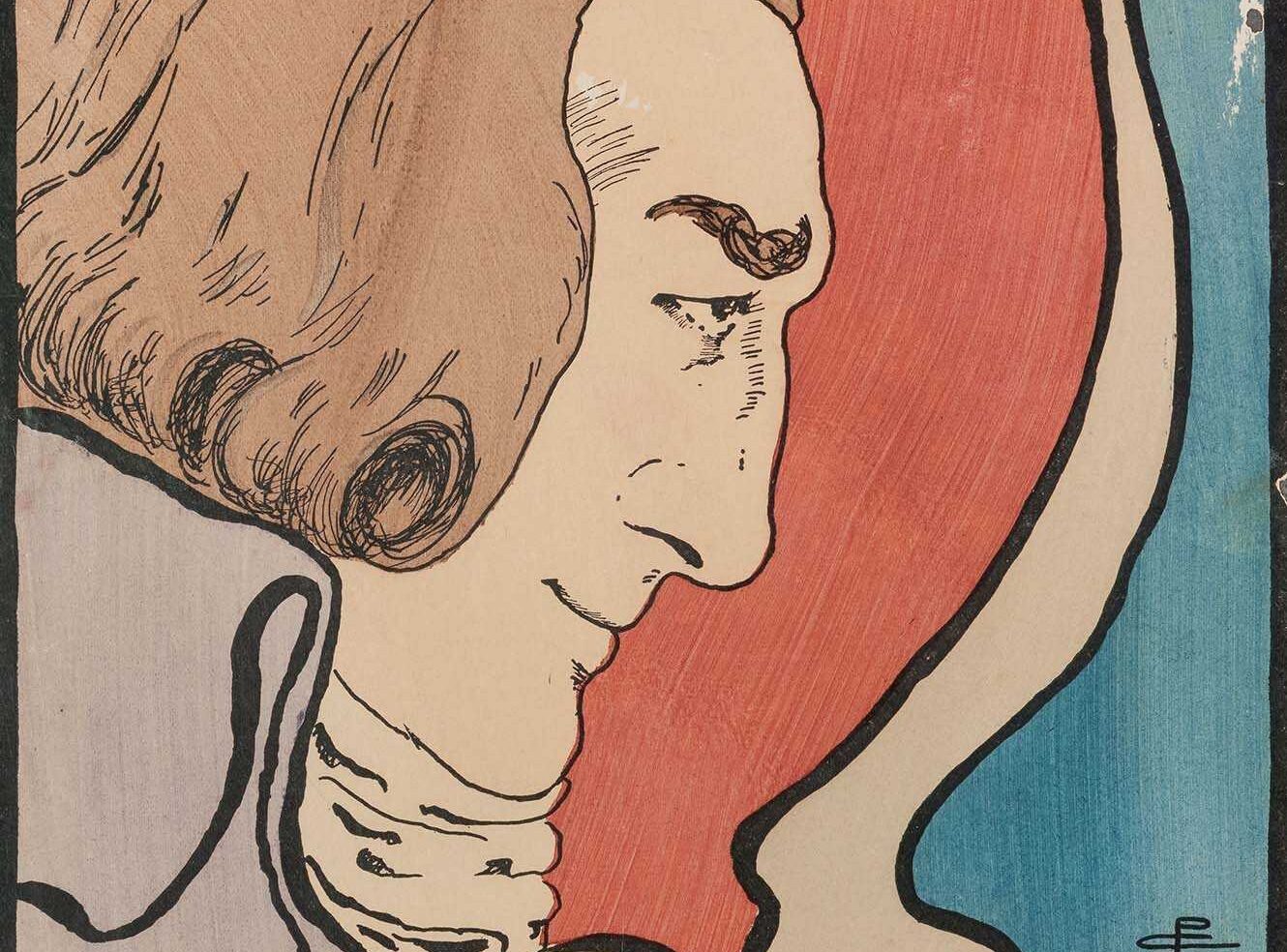

The Nineteenth Century Stage is a rich resource exploring the theatrical celebrities, artistry, and changing social roles of the era. It highlights Pamela Colman Smith, known for her Rider-Waite tarot illustrations and theatre work, whose influence shaped Victorian theatre. Despite being overlooked, her life and impact are vividly captured through striking art and intimate collections within this valuable resource.