Dance with the Devil: William Ellis, missionary, and Hawaiian hula

To the mind of the twenty-first-century tourist, Hawaiian hula dancing is symbolic of Pacific island paradise. Against a backdrop of golden sands and blue waters, we envision dancers bedecked in grass skirts, moving effortlessly to lilting ukuleles. However, if we travel back almost two hundred years, to over a century before Hawaii became an American state, we see the hula at the centre of a moral battleground.

Consider the writing of British missionary William Ellis, who arrived at the “Sandwich Islands” in 1822, and spent two years touring with American Congregationalists, who had arrived in 1820. Periodically, Ellis’s narrative of Hawaiian “progress” is interrupted by hula dancers: they turn up on one occasion at the end of a successful day teaching Hawaiian children, and on another when he is just about to commence an evening prayer session on the beach. For Ellis, the movements these dancers performed lacked purpose or elegance, described as ‘slow’ and ‘not always graceful’, yet, at the same time, held subversive power. Hula (or hura, as Ellis calls it, following his time in Tahiti) was associated with practices of ancestor and idol worship which appeared to directly contradict Christianity, but perhaps even more importantly, wasted time which islanders could not afford to spare if they aspired to salvation and civilisation. As a long hula dance concluded one evening, Ellis was ‘anxious to address the multitude on the subject of religion before they should disperse; but so intent were they on their amusement, that they could not have been diverted from it’.

Image © California Historical Society. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Ellis was, characteristically of missionaries in the early nineteenth century, from a working-class background in which the values of the gospel were inextricable from hard labour and time management. Hula, in appearing to be simultaneously frivolous and idolatrous, threatened an order in which islanders spent their weeks working and learning, before retreating once a week on the Sabbath for worshipful quietude unfettered by ‘athletic sports’ and ‘noise of playful children’.

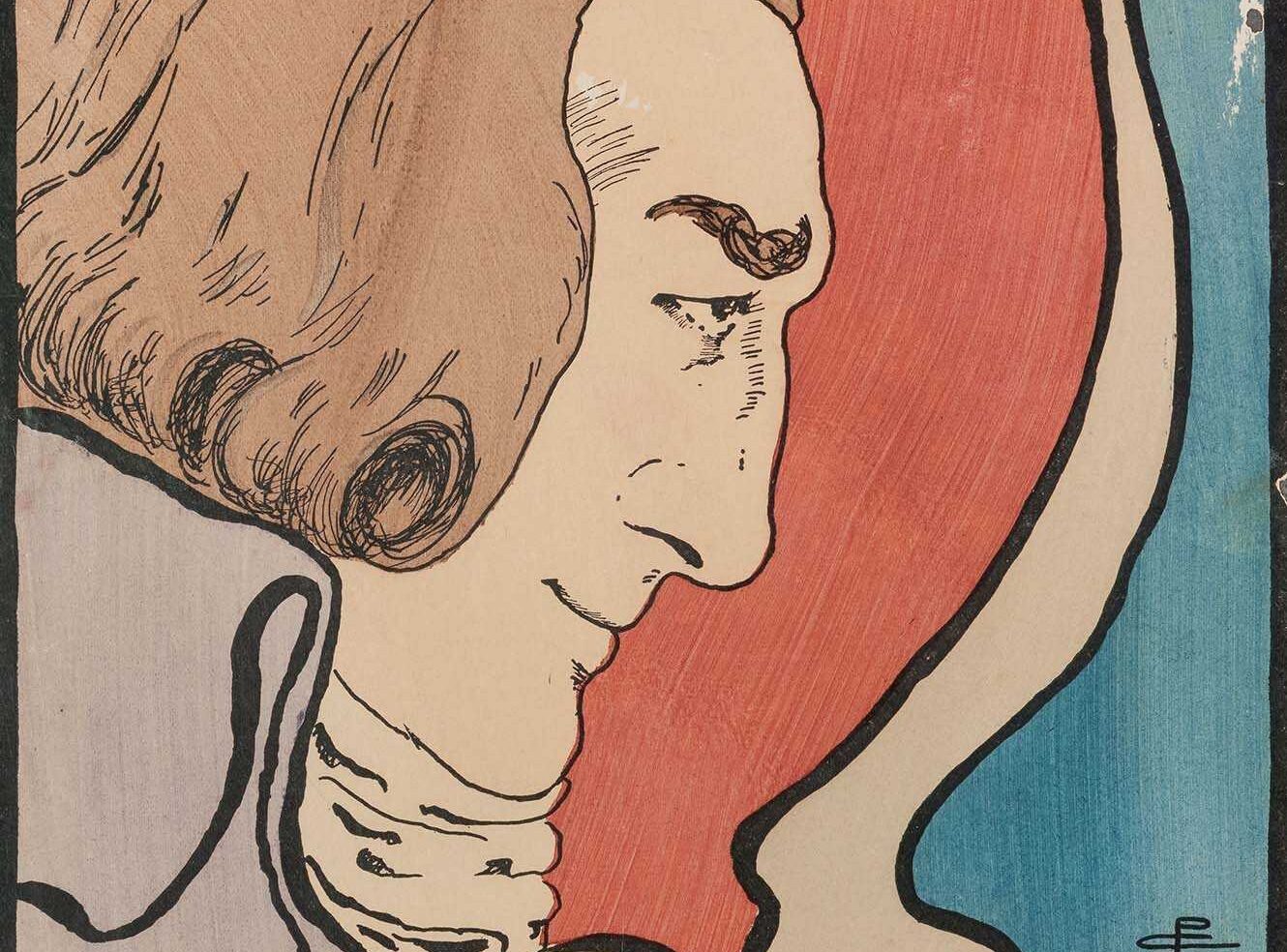

Nonetheless, Ellis saw signs of Christianity’s ultimate victory. He was able to hold his prayer meeting on the beach after all, with the help of the governor of Hawaii island, Kuakini: ‘At the governor’s request, the music ceased, and the dancer came and sat down just in front of us.’ The “heathen” performance was instantly rebutted with a hymn. Furthermore, in the above drawing, we see the same governor, attired in European dress, watching dispassionately as a hula takes place in front of him; for him, at least, it seems to have lost any power, and the scene depicted below suggests that others were becoming similarly attentive to the new order.

Image © California Historical Society. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Ellis was in fact relatively reserved in his condemnation of the hula: an American colleague proclaimed that it was ‘designed to promote lasciviousness’, that it ‘could not flourish in modest communities’, and that it was enmeshed with ‘superstitions’, while Christian monarch Ka’ahumanu prohibited it altogether in 1830. The version of hula which reemerged as a tourist spectacle was quite different, informed by Christian morals and Western musical harmony. Whether islanders themselves ever really drew the same distinction as missionaries between the "old" and the "new", however, is open to question.

Ellis’s account of his Hawaiian tour, plus much more on America and Hawaii in the nineteenth century, can be found in our China, America and the Pacific resource.

Recent posts

Foreign Office, Consulate and Legation Files, China: 1830-1939 contains a huge variety of material touching on life in China through the eyes of the British representatives stationed there. Nick Jackson, Senior Editor at AM, looks at an example from this wealth of content, one diplomat’s exploration of Chinese family relationships and how this narrative presented them to a British audience.

The Nineteenth Century Stage is a rich resource exploring the theatrical celebrities, artistry, and changing social roles of the era. It highlights Pamela Colman Smith, known for her Rider-Waite tarot illustrations and theatre work, whose influence shaped Victorian theatre. Despite being overlooked, her life and impact are vividly captured through striking art and intimate collections within this valuable resource.