Fashioning the frontispiece: The role of clothing in the travel narratives of Isabella Bird

This special guest blog was written by Edward Armston-Sheret and Innes M. Keighren of Royal Holloway, University of London, to celebrate the launch of Nineteenth Century Literary Society: The John Murray Publishing Archive.

At first glance, Isabella Bird (1831–1904) was an unlikely candidate for the role of intrepid explorer. She stood just four feet eleven inches tall and, from a young age, suffered from a debilitating spinal condition that necessitated frequent periods of rest. Nevertheless, Bird travelled the globe in search of adventure, knowledge, and improved health, visiting, among other destinations, Hawaii, the United States, Japan, Korea, China and Tibet. In spanning the globe, and in challenging the limits of her body and societal expectations of her gender, Bird became one of the most celebrated nineteenth-century women travellers and published numerous travel narratives with John Murray. [1]

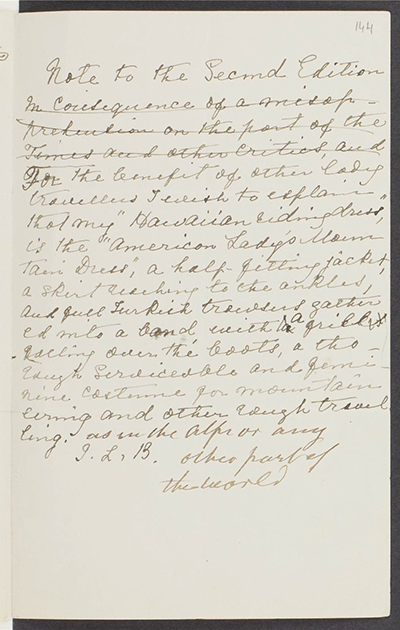

While much has been written about Bird’s remarkable achievements as a traveller, less attention has been given to the role that dress played in how Bird chose to represent herself in her published accounts. Dress was an important issue for women travellers in the nineteenth century. How a woman chose to dress while travelling overseas could make or break her reputation. When one reviewer of Bird’s 1879 book A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains claimed that Bird had donned “masculine habiliments for her greater convenience” on her journey through the Rocky Mountains, Bird dismissed the accusation as “libellous”. Conscious of the slight to her gender, Bird penned a clarifying note for her publisher, John Murray, which can be found in the newly released collection, Nineteenth Century Literary Society: The John Murray Publishing Archive. [2] Included in future editions of her book, the note explained that her “riding dress” was, in fact, a “thoroughly serviceable and feminine costume” and was, moreover, the default “American Lady’s Mountain Dress”. From its second edition, A Lady’s Life featured this correction along with a “rough sketch of the costume” as a frontispiece to further illustrate the feminine appropriateness of Bird’s riding outfit. (See above.) Here, we see that Bird was anxious to construct an authorial identity appropriate to her gender and social status and that both of these considerations were seen to depend, in large part, on the clothes she wore.

In the 1890s, Bird visited China where she adopted both Chinese and Manchu dress. European clothing, she found, attracted unpleasant and unwanted attention. Bird praised the “extreme comfort” of Chinese dress, particularly because it had “no corsets or waist-bands, or constraints of any kind”. [3] Adopting Chinese costume not only offered Bird physical comfort and freedom from scrutiny, but also increased her personal safety. The “capacious garment” she wore allowed Bird to hide her revolver beneath it, concealed in a “very pacific looking cotton bag”. [4] Bird wanted to have the weapon to hand because of the tense political situation in China at the time; her outward appearance belied her inner determination.

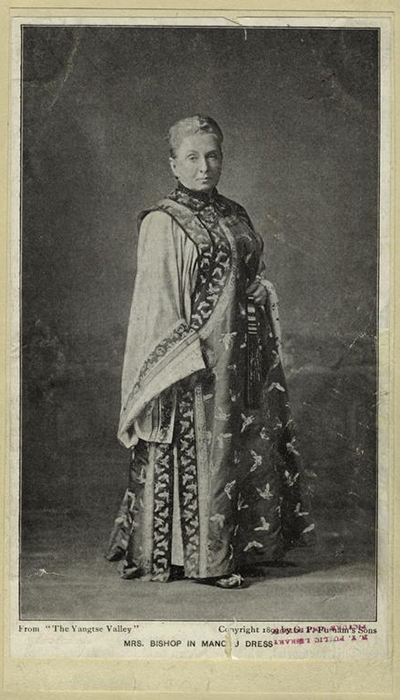

Bird returned from China with various garments that she wore at dinner parties in Britain—an outward symbol of her cosmopolitanism and worldly experience. [5] Bird’s 1899 book The Yangtze Valley and Beyond included a portrait of her in “Manchu dress”. Incorporating an illustration of an explorer-author in non-European dress was a common feature in travellers’ accounts from this period and served, in this instance, to illustrate Bird’s hoped-for position as a sophisticated cultural go-between. In the first printing of The Yangtze Valley, the portrait appeared deep inside the book, but was elevated to the frontispiece in the 1900 edition with the likely intention of bolstering, visually, Bird’s intended status “as a serious and involved negotiator of both Chinese geography and culture”. [6]

Travel allowed Bird to use and dress her body in ways that were impossible at home; wearing different kinds of clothing while travelling highlighted the constraining nature of nineteenth-century British dress codes, particularly for women. But Bird was also careful in how she dressed and represented her body—both overseas and at home, in person and in print—and took seriously the role clothing played in the making of her identity as a woman, an explorer, and an author.

- Bird married in 1881 at the age of fifty and took her husband’s name, Bishop. Some of her later travel narratives were, therefore, published under the name Mrs J. F. Bishop.

- Isabella Bird to John Murray, 21 November 1879 accessed via Nineteenth Century Literary Society, (Marlborough: Adam Matthew, 2020)

- Isabella Bird, The Yangtze Valley (London: John Murray, 1899), 242.

- Ibid.

- Anna Stoddart, The Life of Isabella Bird (London: John Murray, 1906), 350.

- Elizabeth Chang, Britain’s Chinese Eye: Literature, Empire, and Aesthetics in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010), 165.

Nineteenth Century Literary Society: The John Murray Publishing Archive is available now and includes a wealth of primary sources dedicated to Isabella Bird and other travellers of the period.

For more information or to sign up for a free trial, email info@amdigital.co.uk

Recent posts

Jennifer Wedge, AM's Metadata and Discovery Manager, explores the importance of metadata and how it is essential in helping users discover our collections.

Film offers more than entertainment, it captures fleeting, candid moments that reveal the rhythm of everyday life in the past. Wanderings in Peking, from AM’s China on Film: Twentieth Century Sources from the British Film Institute, offers a glimpse of 1930s Beijing, revealing a city where tradition meets progress, with the camera often capturing its most compelling stories unintentionally.