Britain's Banished Men

BBC Two’s newest period drama Banished sheds light on the lives of the first penal colony established in Australia. The likes of Russell Tovey, Julian Rhind-Tutt, and MyAnna Buring portray the lives of convicts and soldiers trying to serve their time and get by in the wilds of New South Wales. Life seems incredibly brutal in this environment and one would imagine the real lives of the first convicts and soldiers would have been terribly difficult. Our upcoming collection, Migration to New Worlds, features a selection of journals from The National Archives UK kept by surgeons on board convict ships to Australia in the nineteenth century. They provide a glimpse into this, often neglected, dubious period of the British justice system.

Image © The National Archives. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Dr William Smith’s account on board the convict ship “Merchantman” outlines the day to day lives of her passengers. It includes their rigorous cleaning schedule, accounts for provisions and meals, and also any infractions by convict, soldier, or crew throughout the journey. It seems that if you were insolent: your wine was stopped. If you stole anything: your wine was stopped. In one case, a convict tried to give a soldier a counterfeit sovereign: his wine was stopped, as was the soldier’s grog. Another more sinister punishment that often accompanied stopping a convict’s wine was being sent to the “black box”. This is, just as you’d imagine, a small box where convicts would have to spend the night, or sometimes longer, as penance.

Food, understandably, seems to have been a constant source of trouble for the convicts. During one of Dr Smith’s journeys on the “Merchantman” some of the convicts cut through the deck into the hold in order to steal food. Twenty two convicts were suspected of this and denied any knowledge. One convict, Charles Kemble, took all of the blame upon himself and stated he did it because he could not subsist on the ship’s allowance. All twenty two were placed in hand-cuffs and Kemble had his wine stopped for the rest of the voyage.

Although the provisions on board convict ships were most likely meagre, it would seem from these ship surgeon accounts, that the actual voyage to Australia was not the part most likely to kill you. As we can see from the list of passengers at the start and end of the voyage, very few convicts were lost. That’s most likely because of the rigorous controls enforced by the surgeon; particularly in terms of cleanliness. All of the bedding was brought on deck, cleaned and aired once a week and the sleeping quarters were cleaned then as well.

Convicts’ daily routine aboard the “Merchantman”. Image © The National Archives. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

No, as a convict heading for Australia’s fledgling colonies, the voyage would have been the easy part. It’s more likely that trouble would start once disembarked at the other side and (spoiler alert for those of you not up to date with Banished) . . . dealings with the local blacksmith, an inability to stay away from women, or ill-fated burials at sea were far more likely to mean the end of the line for some convicts.

Migration to New Worlds: The Century of Immigration will be available from November 2015.

Recent posts

Foreign Office, Consulate and Legation Files, China: 1830-1939 contains a huge variety of material touching on life in China through the eyes of the British representatives stationed there. Nick Jackson, Senior Editor at AM, looks at an example from this wealth of content, one diplomat’s exploration of Chinese family relationships and how this narrative presented them to a British audience.

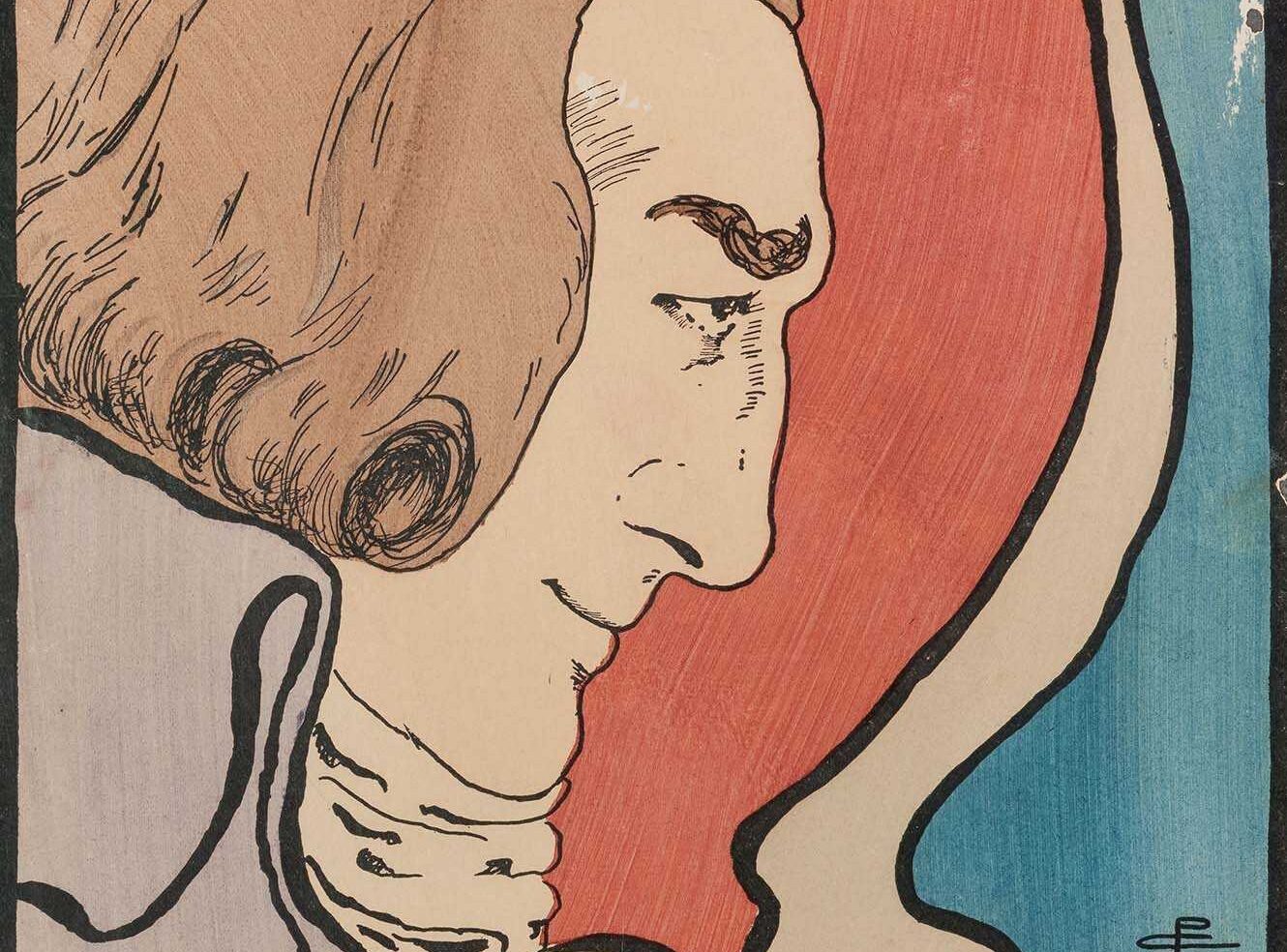

The Nineteenth Century Stage is a rich resource exploring the theatrical celebrities, artistry, and changing social roles of the era. It highlights Pamela Colman Smith, known for her Rider-Waite tarot illustrations and theatre work, whose influence shaped Victorian theatre. Despite being overlooked, her life and impact are vividly captured through striking art and intimate collections within this valuable resource.