Balancing archival processing with digital public access

Is there a way of achieving more product through a different process?

Back in 2005, when Mark A. Greene and Dennis Meissner’s influential article, “More Product, Less Process: Revamping Traditional Archival Processing” was published in The American Archivist, their recommendations were driven by the backlog upon the backlog of physical materials languishing in archival workflows, inaccessible to the public.

The business case for change was, and remains, compelling, juxtaposing the needs of researchers against the craftmanship and science of cataloguing and preservation; arguing for the precedence of access and interpretation of these historical materials, even without detailed descriptions and metadata, over meticulous, traditional methods of processing that would keep these treasures behind closed doors until time or resources allow.

Despite the ongoing challenge of putting it into practice, More Product, Less Process, or MPLP, is widely accepted and practised in physical archives the world over.

Much can be said about MPLP but let’s consider how we can interpret its methodology when it comes to creating digital collections.

An MVP approach to digital objects?

Archives have traditionally relied heavily on metadata and the detailed descriptions included in finding aids to enable researchers to explore collections and identify relevant resources.

At Adam Matthew, our curated primary source collections are lauded for the care and attention to detail that our editors are able to give to these very concerns.

Typically, individual materials are selected for digitisation, then digitised, ingested into a digital asset management system, indexed and published for public access, or, in other cases, to a closed user group.

In short, the very act of digitising source material requires a degree more of the arrangement, description and preservation that Greene and Meissner argued was strictly necessary.

In an ArchivesHub blog on this theme, Jane Stevenson notes that, in order to address the archival backlog, MPLP requires:

a ‘golden minimum’ for processing, where we adequately address user needs and only go beyond this where there are demonstrable business reasons.

But this MVP (Minimum Viable Product) approach is still an interesting concept to consider when planning out the assets that might make it into your online repository.

Enter Artificial Intelligence

Much has been said lately on social platforms and the media about the balance of technology and human input. Across sectors, real fears persist that artificial intelligence will take over from human input into detailed, technical processes. But what if there is a way to balance the two?

As an example, digitised manuscripts lacking a comprehensive description or thorough metadata still abound in research value, according to their type, provenance or subject matter (or all of the above). As archivists and special collections librarians, we know these materials would be welcomed by researchers, if they could but be widely accessed. This is where AI technology can make a real impact.

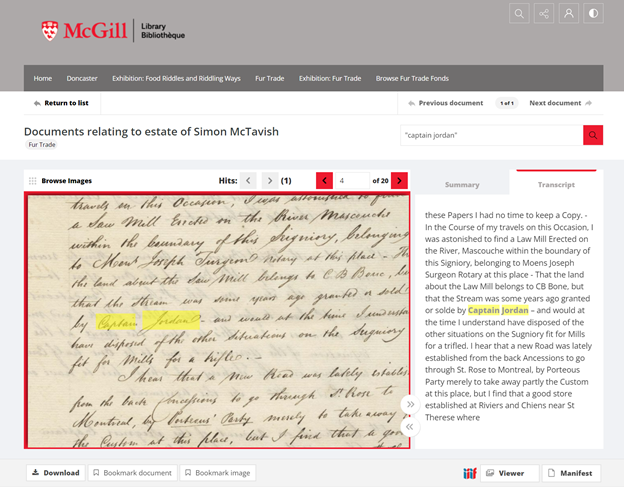

AI-driven Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) can be applied to digitised manuscript images, making the document full-text searchable. Imagine – publishing the document to your digital collection site with a brief description and minimal metadata – but that document being completely searchable for any word, term or name that your users happen to search.

HTR can also generate a transcription – already highly accurate, depending on the image quality, and editable for complete accuracy. The transcription creates a further data set for search and the user’s experience is enhanced beyond what comprehensive metadata alone could achieve.

The transcript also adds a layer of accessibility to the research, rendering the document of greater value to those with limited manuscript literacy skills and those with impairments that may otherwise prevent them from engaging in such research.

In addition, HTR – or rather the full-text search that it enables – can uncover hidden voices within documents. This expands the research scope of such materials to a much greater extent than even the most meticulous cataloguing could achieve, while simultaneously addressing the issue of unintentional bias that easily occurs when cataloguing using traditional taxonomies.

The same is true of printed text materials, and audio-visual files which can have searchable, timecoded closed captions automatically generated and applied.

Full-text search also comes into its own if your community engagement strategy includes inviting users to submit their own contributions of digitised documents, such as letters, journals, or scrapbooks, which are highly unlikely to be accompanied by professional standards of metadata or item descriptions of a quality that ordinarily would be deemed satisfactory in an archival setting.

But what role does that leave for human intervention?

Balancing priorities and user needs

The beauty of making such resources available online in an easily accessible digital asset management system is that each item’s data can be regularly updated. Just as many physical collections are served by a finding aid and described at more global levels, digital assets don’t always have to be complete upfront to have value for the end user, so long as the provision is adequate and functional.

However, with more time and/or resources, further processing of those materials may continue offline and new descriptive data be applied to the digital copy, enhancing search and discovery.

A further role which digital archives can play in backlog management is through an on-demand approach to digitisation.

If other priorities prevent you from satisfactorily processing digitisation candidates, a finding aid can be published to your digital platform containing metadata-only records relating to those shortlisted materials. The obligation is then on users to identify and propose specific items for digitisation. This approach provides direct user intelligence on which materials are of most interest and removes the burden of delivering a complete digitisation service.

Assessing the provenance, significance, condition and preservation requirements of new acquisitions or your interminable backlog will always form an intrinsic function of your service. But a balance needs to exist between this and fulfilling the other key responsibility of making resources available to researchers and showcasing their significance (and by extension that of your repository) to the scholarly community and the world in general.

There are many documented examples of digitisation projects that have stayed true to the MPLP philosophy, with resulting increases in materials made available and, consequently, discovery and usage.

What if it were possible, over time, through the medium of digital archives, to achieve more product through a different kind of process?

Recent posts

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.