“My” American Declaration of Independence: A special guest blog by Joseph J. Felcone

Joseph J. Felcone is a bibliographer of early American printing and has spent time working with the material that will be included in AM's collection Colonial America.

In October 2008 I was spending a week at The National Archives, Kew, recording their holdings of New Jersey imprints for a then forthcoming descriptive bibliography of printing in New Jersey before 1800. The CO 5 records from the British Colonial Office records are an extraordinary source for early American printing, but they have been largely neglected by printing historians because there is no item-level cataloguing. One must call up the large bound volumes that are most likely to yield results and then physically search each volume, page by page, looking for printed material. It’s a time-consuming process (and, happily, soon to be a thing of the past once AM’s Colonial America digitisation project, which will catalogue all 1,450 CO 5 volumes, is completed).

In advance of my arrival I placed a bulk order for about sixty volumes. Each day, from the moment the room opened until it closed, I turned pages, recording New Jersey printing—in several instances finding hitherto unknown examples.

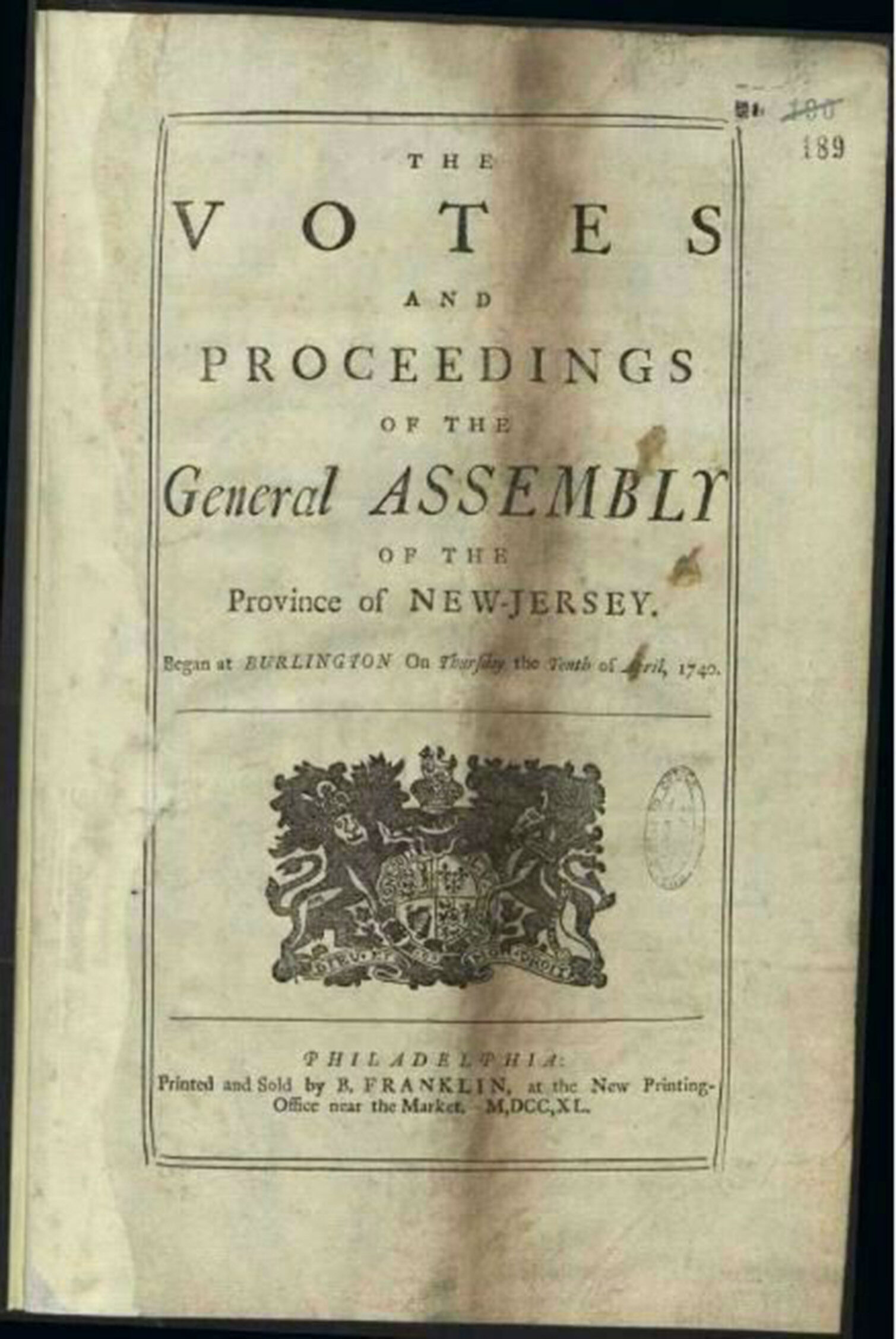

Votes and proceedings of the general assembly of t..., 10 Apr - 31 Jul 1740, © Crown Copyright documents © are reproduced by permission of The National Archives London; UK

It was my last day, and my flight back to the States left early that evening. Too many unexamined volumes remained on the cart. I increased my speed. When these volumes were assembled—in the early nineteenth century, I believe—large sheets such as printed broadsides were folded, in half or in quarters, before they were tipped into the bound volumes. The unprinted side of the sheet is what faces out, but the impression of the type into the paper is clearly visible in reverse, telling the historian of printing to unfold that sheet. It was now early afternoon, and there were still several volumes to go. I came to a large broadside, folded into quarters. I unfolded the top corner just enough to see the text: “In Congress, July 4, 1776. A Declaration… ”. Nope, not New Jersey. And I quickly moved on. After turning several more pages, however, something told me to go back and see if the Declaration was a Dunlap printing—the first printing of the Declaration of Independence, by John Dunlap of Philadelphia. I did, and it was.

Now what? I had just discovered a hitherto unknown copy of one of the most important and iconic American historical documents. The last one to come on the market had sold at Sotheby’s for over $8 million. If I told the archivists of my discovery, there would be some commotion, precious time would be taken up, and, most important, the volume would be swept away before I could finish it. So I refolded the document and went back to the business at hand. Happily, I completed searching all my selected volumes with a bit of time before I had to leave. I told the head of the colonial records section of my discovery, and the volume was taken to the conservation department, where the broadside was carefully removed. The 26th known copy of the Declaration now resides in The National Archives’ Safe Room, where it joins two other copies of the document. To The National Archives it may just be their third copy, but to me, it’s “my” copy of the Declaration of Independence.

For more information about Colonial America, including free trial access and price enquiries, please email us at info@amdigital.co.uk.

Recent posts

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.