‘The captain-general of iniquity’: The impeachment of Warren Hastings

Warren Hastings painted by by Johann Zoffany, 1783-4. From Wikimedia Commons.

One of the many good things about living in a place like Britain, where lots of documented stuff has been going on in a small space for a long time, is that wherever you go there’ll be some historical notable who’s been there before you. Last summer I was wandering around the Cotswolds and passed through Daylesford, for many years owned, I discovered using the power of the guidebook, by Warren Hastings, perhaps the most notorious figure in the East India Company at the height of its power and the penultimate man to be impeached before the British Parliament.

Our new East India Company resource contains plentiful material on Hastings’s very long and very public ordeal. From fairly humble beginnings he had risen to great influence and a considerable fortune; he joined the Company as a clerk, sailing for Calcutta at 17, and by 40 was governor of Bengal. In 1774 his authority was extended over British India’s other governors, making him de facto the ruler of it all – and British India was, of course, most of India.

Westminster Hall, where Hastings's trial took place, by Augustus Pugin and Thomas Rowlandson, 1808. From Wikimedia Commons.

However, nobody rises so high without making enemies along the way. Hastings’s India was beset by constant warfare, for which enemies of the government of the day blamed him; in particular he had long attracted the ire of Edmund Burke, source of the quotation in the title of this post, who held that British rule in India had been destructive and who chaired the Parliamentary select committee on East Indian affairs. When Pitt the Younger became prime minister in 1783 his opposition disheartened Hastings, already in failing health and affected by his wife’s absence in Britain, and he decided to resign and return home – whereupon he was dragged before Parliament, largely at Burke’s behest, and made the centre of a trial on charges of corruption and oppressive treatment of certain Indians which lasted for seven years and at the end of which he was wholly acquitted.

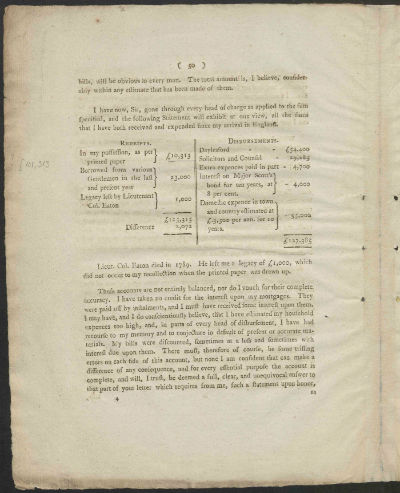

Hastings's tabulation of his finances in his response to Sir Stephen Lushington, 22 September 1795 (British Library IOR/D/254). © The British Library Board. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. To see this document in the collection click the image.

Hastings’s defence, however, had cost him £70,000 – £6.5 million today – threatening his beloved Daylesford, the medieval seat of his ancestors, which he had bought back for his family (although, it has to be said, in the middle of his trial) and whose manor house he had had rebuilt in a magnificent decorative style inspired by his time in India. Among the papers on Hastings’s trial in East India Company is a long report on what might constitute a fair response to the fact that he had more or less bankrupted himself in answering charges of which he was found not guilty. The gist is that the directors of the Company have voted to reimburse for his trouble the man who has served them for 31 years but that legislation constraining their freedom of action prevents it. The chairman, Sir Stephen Lushington, writes to check he really is as penurious as he says (remember, it was the eighteenth century):

I have, Sir, no pretensions in my individual capacity, to enquire into the state of your private affairs; I should think myself impertinent so to do; but, as Chairman of the East-India Company, anxious for the honour and character of their Servants of every description; especially those who have held such high and confidential offices, I have taken upon myself to desire of you to state to me in writing, upon your honor, a full, plain, and unequivocal account of your fortune, for the purpose of availing myself, if I see a fit and proper occasion, for removing those doubts, which, I must repeat, do at present exist in the minds of persons of distinguished honor and character.

To which Hastings replies that apart from his home he has a diamond and shares in two ships, but no ready money.

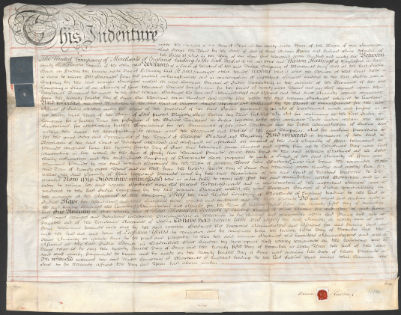

The indenture between the Company and Hastings guaranteeing his annuity, 7 April 1796 (British Library IOR/A/1/86). © The British Library Board. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. To see this document in the collection click the image.

The Company failed in their efforts to pay their man’s legal fees, but they did grant Hastings an annuity of £4,000 a year, backdated to when he first set foot in Plymouth on his return from India. However, he continued to spend money he didn’t have, and was technically insolvent on his death in 1818. Daylesford, meanwhile, has once more slipped out of the hands of the Hastings family: it is currently the home of Lord Bamford, chairman of JCB.

Module 1 of East India Company is available now. For more information, including free trial access and price enquiries, please e-mail us at info@amdigital.co.uk.

Join the webinar on East India Company on 25th January to discover more about the resource.

Recent posts

In preparation for migration to AM Quartex, the University of Delaware Library, Museums and Press had to take stock of and rationalise seven distinct digital collections. Learn about how this was overcome in part three of this guest blog series.

From medieval markets to a global powerhouse, London’s evolution between 1450 and 1750 is vividly documented in the records of its livery companies. Central to the city’s economy, these institutions reveal how London navigated challenges like plagues, the Great Fire, and rapid growth, underscoring their vital role in shaping a thriving metropolis.