Building Bionic Men; Replacing Limbs Lost in WWI

‘Wouldn’t it be a triumph – a true croix de paix – if the returned soldier could date his success in life from the event that seemed at first an unbearable misfortune?’

After the guns fell silent on 11/11/1918 and the global conflict now known as the First World War drew to a close, millions of servicemen could look forward to returning to their countries of origin, being reunited with their families and resuming the lives they had held before enlistment.

For many, however, this return to pre-war normality seemed a physical impossibility. According to contemporary data from the French and British governments, around 1 in every 7 soldiers was discharged after receiving life-changing and debilitating injuries during the war. Rapid developments in innovative technologies of destruction such as the machine gun, explosives and chemical weapons had left tens of thousands of soldiers permanently maimed and disfigured.

A prosthetic arm with an articulated hand being used to play the violin. Image © New York Academy of Medicine. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Cautious of both a massively depleted workforce and the immense cost of caring for war invalids, the race began amongst the combatant countries to repair, repatriate and re-employ their disabled veterans. The governments of Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Great Britain, New Zealand and the U.S.A. all established repatriation commissions to oversee the process of returning these men to society.

A major part of the work of these commissions was to fund the provision of artificial limbs to replace those lost during the war. To answer this new demand rushed an assortment of doctors, scientists, inventors, entrepreneurs and outright opportunists all racing to patent the definitive artificial limb and claim the cash prizes for the best designs.

Before the war, prosthetics had largely been heavy, unwieldy implements carved from one single piece of wood. Much emphasis was placed, by both medical reports and articles by institutions such as the Red Cross, on returning the maimed soldier to vigorous industrial or agricultural work, so that he might have ‘not charity, but a chance’. To achieve this end, new prosthetic limbs were designed to be light-weight, functional and, above all, comfortable to use in everyday labour.

Whilst industrial utensils could quite easily be affixed to bionic extensions of limbs, a greater challenge came in the search for practical substitutes for fingers and joints. One solution proposed by Italian surgeons was the forming of a ‘motor flap’ from the muscle and skin of an amputee’s stump. This flap, once attached to ‘hooks, wings, rods or thongs’ could be contracted to induce a movement in the prosthetic limb, closing a hand or bending a joint. The effectiveness of this technique, as the report concedes, was entirely dependent on the amount of tissue left to the amputee after surgery. Thus, a great level of co-operation between surgeon and engineer was required.

An article illustrating the process of creating ‘motor flaps’. Image © New York Academy of Medicine. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

The credibility of these innovations in functioning prosthetics ranges widely. An issue of Popular Mechanics Magazine (‘written so you can understand it’) published in February 1919 claims that a new mechanical hand and forearm could hold a cigar, remove a hat, adjust glasses and even operate a shaving razor with complete safety - all under the operation of only one pull cord. The article goes on to claim that an amputee using this hand is fully capable of bouncing, and then subsequently catching, a rubber ball against a wall or floor.

An advertisement for a natural-appearing prosthetic hand. Image © New York Academy of Medicine. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

The emphasis of these advertisements on the ‘natural appearance’ of their artificial limbs marks a clear departure from the ‘not for looks, but for use’ limbs intended for working class agricultural and industrial laborers. Aesthetics were also a primary concern in facial prosthetics, which were designed to mask the scars and deformities of returning soldiers.

An arrangement of facial prosthetics used to rebuild damaged faces. Image © New York Academy of Medicine. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Whilst facial prosthetics may have brought some comfort to disfigured veterans, the point re-iterated by both the Red Cross, medical reports and government commissions was that the best method for returning disabled veterans to a plausible sense of normality was to return them to work.

Functioning prosthetics marked the first step in a multi-staged process of repatriation, which included the vocational training, re-education and re-homing of returning veterans. Ever conscious of this ultimate end goal, many prosthetics manufacturers led by example and drew their work force exclusively from the ranks of the disabled veterans that they were manufacturing for.

‘These five employees of the plant have but three natural legs between them’. Image © New York Academy of Medicine. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Medical Services and Warfare; Module I: 1850-1927 will be available from Autumn 2017 http://www.amdigital.co.uk/m-products/product/medical-services-and-warfare/ For more information, including free trial access and price enquiries, please email us at info@amdigital.co.uk.

Recent posts

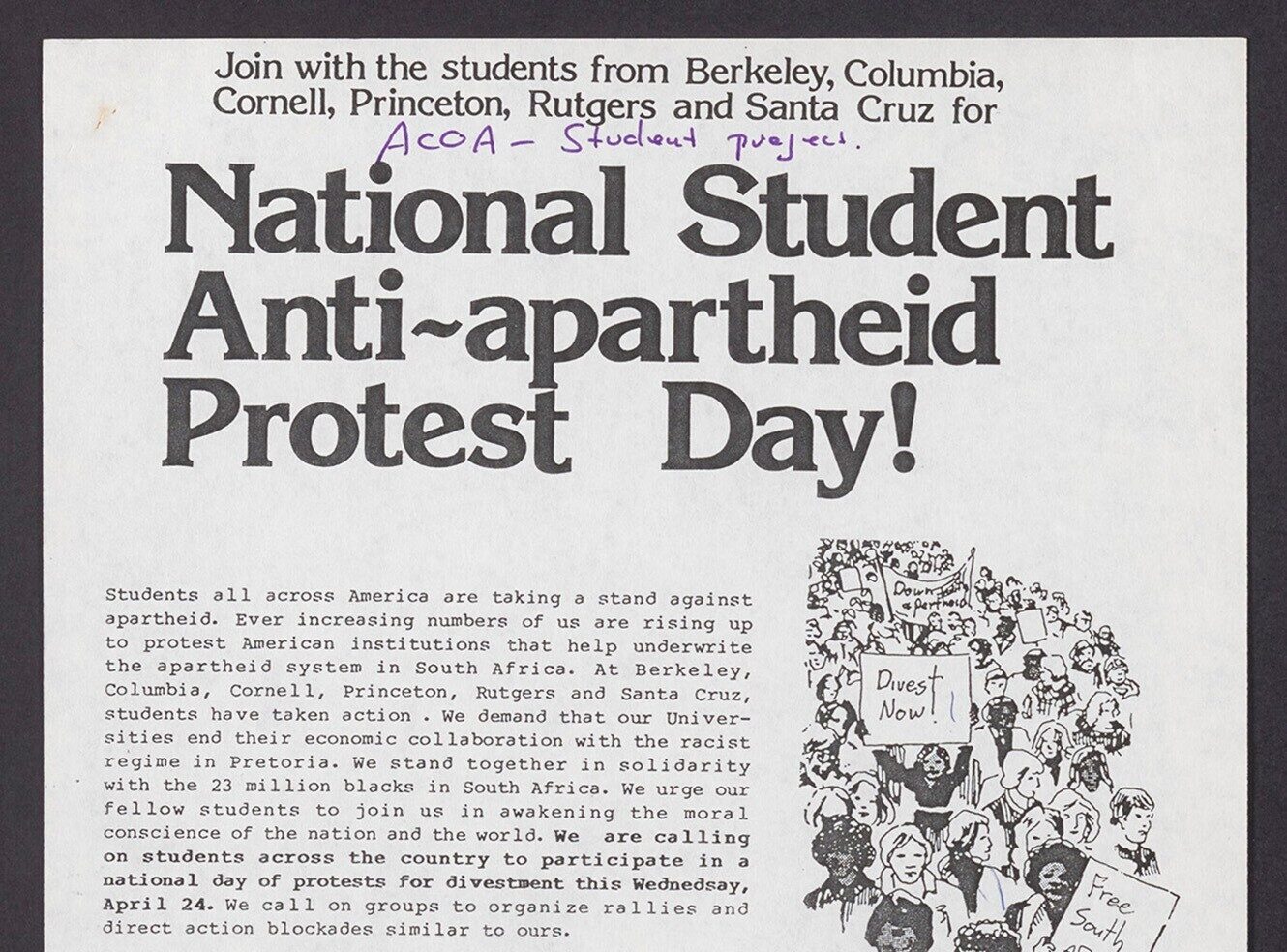

The blog highlights American Committee on Africa, module II's rich documentation of anti-apartheid activism, focusing on the National Peace Accord, global solidarity, and student-led divestment campaigns. It explores the pivotal role of universities, protests, and public education in pressuring institutions to divest from apartheid, shaping global attitudes toward social justice and reform.

This blog examines how primary sources can be used to trace the impact of young voices on society, particularly during pivotal voting reforms in the UK and the US. Explore materials that reveal insights into youth activism, intergenerational gaps, and societal perceptions, highlighting their interdisciplinary value for studying youth culture, activism, and girlhood across history.